Want to create more trust in every corner of your organization? The strategy is simple: Start making more mindful choices.

By Kenneth M. Nowack, Ph.D., and Paul J. Zak, Ph.D.

We are, by our very nature, social creatures who are biased to feel greater safety with others most like us. Biases are automatic associations that may arise during interactions with others. Even though an association between a group and specific stereotypes may exist, it doesn’t mean you’ll necessarily behave with mistrust or intentional animosity toward others. But biases can and do cause unintentional, unfair, and discriminatory treatment of others.

To change behavior in yourself or in others, you need to be aware of biases and blind spots to make decisions and take actions in a purposeful manner. Here then, we offer a new model of bias, explain the neurological origins of many biases, and make evidence-based suggestions for facilitating what we call mindful choices (conscious bias) in the workplace.

The Bias Iceberg Model

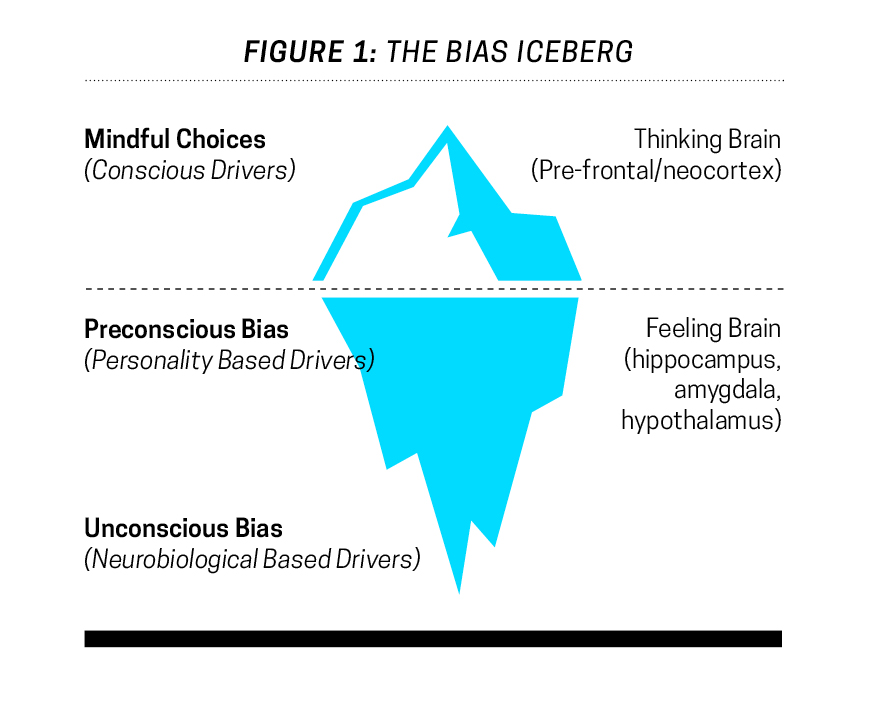

Our Bias Iceberg Model (Figure 1) expands on some of our recent research and provides a way to conceptualize the layers of bias that permeate all social interactions we have each day. The first level is activated by brain structures largely outside of conscious awareness and functions automatically, so we use the popular term “unconscious bias.” Its main purpose is to keep you alive and physiologically functioning by heightening defenses against real or imagined threats (e.g., fight-or-flight stress response).

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

We call the second level “preconscious bias,” because while they also function automatically, they can be under our control with awareness, conscious effort, and practice. This can be done, for example, by slowing down your actions to assess if there might be negative consequences if your initial impulse is acted upon.

Finally, we use the term of purposeful or “mindful choices” when you can reflect and act on the thoughts, feelings, and beliefs you’re aware of to guide interactions with others. Although work and life stressors mobilize a set of neurologic responses that activate automatically, we can nonetheless be more aware and purposeful with decisions and actions we make each day by embracing mindful choices.

Figure 1: The Bias Iceberg

Unconscious Bias and Neurobiological Drivers

Trust and Empathy Bias

One of us (Zak) was among the first neuroscientists to demonstrate the neuroactive chemical oxytocin instantiates empathy and promotes prosocial behaviors. Oxytocin (OT) is an evolutionarily ancient molecule that’s a key part of the mammalian attachment system that allows us to form and nurture relationships of all types.

Zak’s group showed in numerous laboratory and field experiments that when you’re trusted, your brain produces OT in proportion to the amount of trust shown. Although there are indeed individual and situational differences, in general, OT reduces the innate bias we typically have when interacting with a stranger, signaling it’s safe and often profitable to engage.

Furthermore, OT makes it feel good to cooperate with others. It does this by activating brain networks that potentiate the release of dopamine and serotonin, reinforcing the value your brain places on trusting a stranger.

Intergroup Empathy Bias

Empathetic concern for others and empathetic distress when others suffer is biased toward those in your “in-group.” This bias has both genetic and learned components. From an evolutionary perspective, establishing solidarity with your primary social group increases the chances of surviving against predators and successfully reproducing. Today, each of us belongs to various tribes, clans, and groups from which we form “self-identities.” We typically relate well with those most like us and naturally avoid “outsiders” who might pose a physical or psychological threat to us.

OT infusion studies that prime participants to have an in-group preference or out-group derogation have been published. However, recent investigations by Zak’s lab show individuals who experience an increase in endogenous OT have little or no bias toward out-group members. The exception was those who were strongly religious; their bias was reduced by OT, but not eliminated. The same holds true with OT infusion studies that don’t prime group biases; absent priming, they don’t arise. This finding supports the view that OT reduces in-group biases, especially when taking the perspective of others is required.

Research by John Lanzetta at Dartmouth University investigated psychophysiological, behavioral, and psychological effects during interpersonal interactions. His research showed competitive relationships reduce empathy, while cooperative settings enhance compassion. For example, psychophysiological measures indicated participants in his study had little distress when viewing a painful shock of a competitor, but were distressed when seeing the competitor experience joy.

This finding is supported by research by David Eagleman at Stanford University, who measured neural responses using fMRI while people watched six hands being stabbed with a needle. This triggered empathetic responses for those in the same, but not different, religious group.

As in the Zak study, participants who strongly identified with their religion demonstrated a significantly higher neural response to empathy for the pain of those in their own religious affiliation and a reduced empathetic response to seeing a label identifying the hand as being from another religious group.

Other studies, such as those by Xiaojing Xu and colleagues from the Department of Psychology at Peking University, have also demonstrated similar neural ingroup/outgroup empathy responses based on race and culture.

In addition, there exists evidence for outgroup homogeneity bias. In this bias, we tend to perceive out-group members as homogenous compared to our own in-group members (i.e., we see more variation and appreciate individual differences more in our own in-groups). The open question for leaders of organizations and teams is how to decrease the gap in empathy between in-groups and out-groups that might exist naturally in companies, as well as enhance our understanding and appreciation of the differences within our out-group members.

Preconscious Bias and Personality Drivers

The Playing Well with Others Bias

It’s known that two genes, CD38 and CD157, largely regulate the release of oxytocin. Anne Chong and colleagues at the National University of Singapore studied the social skills of 1,300 healthy young Chinese adults. They found individuals with higher gene expressions of CD38 and variations in CD157 displayed greater sociality (e.g., preferring activities involving other people over being alone), had better communication, and showed empathy-related skills compared with other participants.

The higher expression of the CD38 gene and differences in the CD157 gene sequence explained 14 percent of the differences in “how well participants played with others.” These findings show social behaviors are truly a mix of nature and nurture. The expression of these genes can be affected by your life events, as can situations that cause oxytocin (and the amounts released), directly influencing empathy and collaboration with others.

The Playing Poorly with Others Bias

Previous research by one of us (Zak) found that approximately 3 to 5 percent of individuals who were entrusted with money by a stranger failed to have the expected increase in OT. As a result, they didn’t reciprocate by being trustworthy, keeping all or most of the money they had been sent. About half of these unconditional non-reciprocators have quite unusual personality traits. (The other half, meanwhile, are having a bad day; high levels of stress hormones inhibit the release of OT and thereby prosocial actions.)

The clinical prevalence of “dark side” personality disorders (characterized as a disregard for right and wrong, persistent lying and expressing cynicism, grandiosity, and disrespect for others) is estimated at 1.5 to 2 percent of the population. Twin studies indicate a genetic influence in the disorder, but childhood trauma is also a contributing factor. Individuals with antisocial personality disorder are seldom remediated, and it’s best to get them out of your organization as soon as possible so the cancer of callousness doesn’t metastasize.

The Diversity of Teams and Testosterone Bias

Recent evidence has shown diverse teams are more productive than homogenous teams. But unconscious bias can still slip into the mix and negate the value of diversity. Modupe Akinola and colleagues at Columbia Business School discovered that testosterone levels of individual team members predicted team success. In diverse groups (culture, background, and age), high testosterone was associated with reduced performance by enhancing conflict and competition.

However, groups that lacked cultural diversity and had high testosterone performed significantly better than lower-testosterone groups as the additional energy of testosterone was focused on reaching group goals. Exercises that build relationships in diverse groups may be able to reduce in-group competition and focus the high-energy of testosterone toward meeting the group’s objectives.

How to Overcome Bias and Create High Trust and Empathy Cultures

Inclusion for everyone at work is a necessity, as is reducing bias and increasing diversity. However, some recent studies, summaries, and comprehensive reviews including the Equality and Human Rights Commissionhave highlighted the shortcomings and relative ineffectiveness of diversity and inclusion training to modify attitudes, change behaviors, and enhance trust in teams and organizations. Here are few ways that individuals and organizations can address some aspects of the Bias Iceberg and simultaneously build cultures of high empathy and trust.

Bias-busting tip #1: Become more aware of how fear impacts you. By increasing your own self-awareness about your thoughts, emotions, and reactions to fears, you can begin to modify those evolutionary automatic survival behaviors to those more consciously displayed toward others within the Bias Iceberg levels. Understanding and reflecting on your own learned bias and honestly clarifying the stereotypes you have about others is an important first step to beginning your journey to more mindful and conscious prosocial behaviors with members of your out-group.

Bias-busting tip #2: Practice empathy-based mindfulness meditation. One approach to tame your fears and enhance your compassion and empathy toward others involves the practice of mindfulness meditation. Not all forms of meditation activate the same neural pathways, nor lead to the same outcomes (much like some types of exercise increases aerobic capacity and other types increase strength and muscle mass). The most effective type of meditation to enhance empathy and compassion is known as metta or loving-kindness meditation.

In this form of mindfulness meditation, participants are asked to think of someone they love for 10 to 20 minutes for three months and focus on feelings of care, compassion, and affection toward that person. They’re also typically asked to do the same for people they don’t know very well, and for people with whom they don’t get along.

Bias-busting tip #3: Practice empathy-based perspective-taking. It’s thought that by having employees practice taking another person’s perspective (e.g., asking employees to imagine for a moment they’re another person, walking through the world in their shoes, and seeing the world through their eyes), this increased awareness of others will directly translate to improvement in appreciation and caring of others.

When employees are adept at perspective-taking, they’ll treat others more “self-like,” activating areas of the brain associated with self-focus and self-reflection (e.g., ventromedial prefrontal cortex; vMPFC). Exercises focused on perspective-taking appear to blur the distinction between self and others, enhancing empathetic concern and possibly even reducing unconscious bias and overt prejudice.

Bias-busting tip #4: Encourage healthy lifestyle practices in employees. Interventions aimed at enhancing employee psychological health and well-being of employees could also offer some possible ways to impact empathy, collaboration, and caring in organizations. For example, those of us who lack adequate sleep at night lose our capacity to treat others with caring, empathy and kindness. Additionally, fatigued and chronically stressed employees have a neurological handicap, increasing our biases and interfering with sound decision making and judgment in dealing with others.

When faced with perceived injustice from others, current research supports using exercise as a beneficial coping tool. When employees are faced with leaders who lack sensitivity, caring, and empathy, being physically active might be a useful coping technique to minimize the impact of such toxic behaviors on both performance and well-being when few other options exist.

Bias-busting tip #5: Create, reinforce, and support a culture of appreciation. One important interpersonal leadership skill directly associated with perceptions of empathy and trust is appreciation toward employees. Appreciation at work (e.g., communicating that you value someone else; unconditionally acknowledging another person as an individual; acknowledging performance, qualities, or behavior of others) directly affects employee well-being.

Appreciation is about acknowledging a person’s inherent value rather than focusing on a person’s efforts or accomplishments, and this is something leaders can model and display daily, even with our current work-from-home situation.

Bias-busting tip #6: Create team and organizational empathy-oriented norms. Leaders and teams that create empathy-related norms of behavior enhance greater collaboration, effective communication, and psychological safety. At the organization level, it’s important to share values around empathy and tolerance for differences in the workplace in the initial interview, selection, and onboarding processes with both internal and external job candidates.

Make the Choice

When your brain produces oxytocin while interacting with others, you’re evolutionarily primed and motivated to cooperate and collaborate with others. Infusing people with oxytocin results in marked reduction in fear-associated brain activity. This generally enhances psychological safety and prosocial behaviors except in people with certain socially maladaptive personality disorders. For most people and situations, oxytocin in the brain increases empathy and facilitates giving and helping behaviors.

This explains why we cooperate with those who appear trustworthy and safe, yet our survival instinct means we’re also unconsciously biased toward those who seem different. When people are primed to view others as different, psychological safety is diminished resulting in decreased collaboration.

Recent research from one of our labs (Zak) has shown that even taking a few minutes to get to better understand and know others can induce your brain to release oxytocin. This melts the self-other divide, increasing both empathy and cooperation. Reflecting on the Bias Iceberg model before you say or do something reflexively can raise awareness that mindful biases promote greater fairness, inclusion, and support of diversity in the workplace.

Kenneth M. Nowack, Ph.D., is a licensed psychologist and cofounder of Envisia Learning, Inc. Nowack received his doctorate degree in counseling psychology from the University of California, Los Angeles and has published extensively in the areas of 360-degree feedback, assessment, health psychology, and behavioral medicine. Nowack serves on Daniel Goleman’s Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations and serves as Editor-in-Chief for the APA journal Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice & Research.

Paul J. Zak, Ph.D., founding director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies and professor of economics, psychology, and management at Claremont University, is a leading expert and scientist, author, and speaker. He is credited with the first published use of the term “neuroeconomics” and has been a vanguard in this new discipline. Zak’s lab discovered in 2004 that the brain chemical oxytocin helps us determine who to trust. His current research has shown that oxytocin is responsible for virtuous behaviors, working as the brain’s “moral molecule.” Zak is author of the new book Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High-Performance Companiesand frequent contributor to HBR.