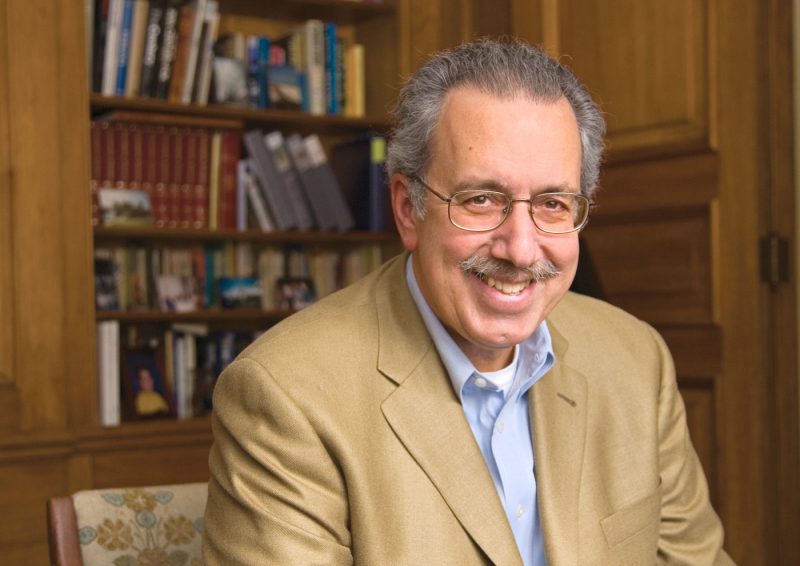

Case Western Distinguished University Professor Richard Boyatzis, Ph.D., reveals his time-tested list of executive musts, goes deep on his landmark leadership research, and sheds light on the evolution of emotional intelligence.

By Marc Effron

TALENT QUARTERLY: Your contributions, in large part, started the organizational shift toward using competencies to assess, develop, and even compensate leaders. It’s been more than 25 years since your book The Competent Manager was published. In what ways has the increased use of competencies helped organizations and leaders be more successful? And how have organizations misunderstood or misapplied the concept?

RICHARD BOYATZIS: The competency movement was kicked off in the mid 1970s by our firm, McBer—which was founded by David McClelland—and PDR (later PDI), which was founded by Marv Dunnette. McClelland et al. had proposed in their 1958 book Talent and Society that competencies could be important as another psychological variable. But it wasn’t until his landmark 1973 article “Testing for Competence rather than ‘Intelligence’” that the competency movement had a name.

The popular definition of the time was “KSAs”—which stood for knowledge, skills, and abilities—and people couldn’t understand why what we were doing was any different than skills. These competencies were bigger than skills. For example, listening is a skill, but empathy is a competency—a set of behaviors related to it, but organized around an underlying, often unconscious intent.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

By the late ’70s, we were on panels at the Academy of Management, the American Psychological Association, and other organizations arguing that competencies were relevant. In 1979, I gave a speech to the APA New York division in which I said competencies can be the DNA of human resource management systems. I told them you could use competencies for selection, promotion, career pathing, creating incentives, compensation systems, and all the placement activities. People were hesitant at the time. But 10 years later, competencies were commonly accepted and used by clients of ours including General Electric, Digital Equipment, and American Express.

Many of our early contracts for those clients included doing the studies that created and validated the competencies. That validation process is critical. It’s not a competency if people sit around and say, “What do we think we need for somebody to be good at this?” In that case you’re going to get the common mythology. That mythology may have elements that are correct, but when we studied that approach, we found half of the things you identify are correct, 25 percent of the things you identify are irrelevant, and 25 percent are exactly the opposite of what predicts effectiveness! If you want to maximize engagement, why would you spend 50 percent of your time chasing the wrong variable?

So when you ask why management still isn’t great after all these decades of research and new knowledge, it’s because many leaders are promoting people who are like them, rather than promoting people who can do the job really well. And when you said people sometimes overuse competencies, my guess is they’re not overusing them— they’re misusing them. There’s nothing wrong with the basic science, models, and methods that McBer and PDI pioneered in the early ’70s.

TALENT Q: You’ve been a key influencer in the creation and popularization of emotional intelligence (EI), which has been widely adopted by leaders, corporations, and consultants. Its popularity has also led to the generic, and sometimes imprecise, use of those words to describe leaders. What would you like the typical executive to know about EI, its benefits, and how it applies to them?

BOYATZIS: When Dan Goleman and I went back over hundreds and hundreds of competency models, it became pretty clear that about 80 percent of the competencies had something to do with how people manage their emotions, and how they manage their emotions in relationships with others. So there are EI and social intelligence (SI) competencies that are quite distinct from one another, even down to the different neural networks that drive them.

When we talk about EI competencies, we’re talking about behavioral habits that enable somebody to manage emotions: self-control, adaptability, achievement orientation, self-awareness. When we talk about SI competencies, we’re talking about the ones that enable a person to effectively recognize and manage the emotions of others and build their relationship’s empathy, inspirational leadership, influence, and teamwork. The only competencies not included in EI and SI that most people encounter are those related to cognitive abilities.

Now, EI isn’t everything. What EI contributes is about 80 percent of the game, but there’s no amount of EI that can make up for a lack of cognitive intelligence. But we can show through empirical studies how EI contributes to key metrics like operating profit. Our 2006 research on a large consulting firm’s senior executives showed that the senior partners who demonstrated more of these competencies more frequently delivered a huge amount of operating profit.

The other thing that research did was affirm something that McClelland alluded to in 1998 when he talked about tipping points. He never said IQ wasn’t important—he said it’s not the end-all or be-all. We now have a number of research studies on cognitive ability that show to be effective at almost every job, you need a certain amount of cognitive capability, EI, and SI. It’s that combination that enables you to be effective.

In 2017, we published a study in Career Development International where we looked at engineers in a very large, global, international manufacturing company. We used peer assessments to measure each engineer’s EI and SI and used the platinum standard of IQ tests (Ravens Progressive Matrices) to measure the engineers’ IQ. It was EI and SI, not IQ or even the big five personality traits, that predicted peers’ measures of which engineers were effective.

What percentage of their effectiveness was accounted for by the emotional and social intelligence behaviors above and beyond cognitive, intelligence, and personality traits? Thirty-one percent. That’s shocking because most people get excited by a 2 to 5 percent difference in research studies, and this study showed 31 percent. It says that engineering is a team sport.

One of my former doctoral students just finished her thesis that showed among high-tech firms, product innovation was predicted by the firm’s collective EI and SI. In short, if you want any degree of adaptation or innovation in your products and services, you have to focus on EI. That’s some pretty strong statistical evidence that shows it really matters.

What do you do about it? First of all, take it seriously. When you consider whether to promote someone, don’t tolerate the fact that they’re a rainmaker but also interpersonal sandpaper. Take it seriously in every promotion decision that you make for managerial or executive level positions. While EI doesn’t mean the person is loved by everyone, it does mean they get along with people.

Second, use it in coaching and development because it’s eminently learnable. We have 39 longitudinal studies showing that 25- to 65-year-olds can develop these behaviors within a year or two, and about 50 percent of the improvements stick even 7 years later. That’s a sign of hope. That says you can help people to develop it.

Do I think you should include it in selection of people into your firms? No. Because if you selected for people’s ability to do everything, you wouldn’t be able to hire or find anybody. I’m talking about promotions to the upper levels and about training, development, and coaching.

TALENT Q: Resonant leadership—the topic of your 2005 book by the same name—seems to build on the emotional intelligence concept. What does it mean, and how can it help leaders and their teams be more successful?

BOYATZIS: Reflect on a leader who brought out the best in you—not who you liked, not who was positive—but who brought out the best in you. They inspired or leveraged or ignited your talent. Then compare that leader to one you’ve worked for who did not. I can guarantee you among the things you’ll identify is that one created a sense of hope, purpose, and vision. One created a sense of caring and trust and seemed to act with integrity and consistency. I’ve done that exercise for 19 years in about 65 countries on all seven continents and nearly every person has answered the same way. So I think most people’s experiences with leaders who bring out the best in them is that they’re in sync with them.

We use the concept of “resonance” to go beyond the old-fashioned notion that somehow the hierarchy is important—that just because the boss says that this is our strategy, everybody has to get behind the boss. That notion is ridiculous and has never been shown to predict effective leadership. Often those who believe in it want obedience, not effectiveness. The notion of resonance means the leaders and the people around them feel like they’re in tune with one another.

We also have functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies that show when people are in those kinds of relationships—where they feel in sync and in tune with the other person—they activate parts of their brain that make them open to new ideas. When they’re with people who are dissonant, two-thirds of the time they activate parts of their brain that close them down to new ideas. Dissonant leaders can get short-term results, but those results aren’t sustainable. And it’s not that they aren’t sustainable over several years; they aren’t sustainable for 6 months.

Our research shows the parts of the relationship that best predict leadership effectiveness, engagement, organization, citizenship, and innovation are shared vision, shared compassion (which really means caring), and shared energy. We now have published studies showing it predicts success in family businesses, in females getting succession, in bank executives’ leadership effectiveness, physician executives being good in health care, and on and on.

EI and SI competencies matter toward these things but they are, in research language, mediated or moderated. They’re transformed by our relationships. Without the relationships, you’re still going to have impact, but it’s going to be less. Our research in both consulting and manufacturing companies showed the amount of EI the team members saw in each other predicted engagement, but the degree of shared vision in their perceived relationships amplified the impact.

TALENT Q: Are there new leadership competencies needed in response to the changing world of work?

BOYATZIS: The short answer is no. Everybody likes to say, “My God, the world is so different.” It isn’t. We’re not seeing any competencies that we didn’t see in the ’80s. Sometimes there’s a slight shift in the potency of each competency. We know teamwork is really important these days and accounts for more than it did in the early ’80s. The same thing is true for adaptability. It’s not that they’re new competencies—it’s that there’s a shift in their weighting.

TALENT Q: When CEOs and board members are surveyed about talent management, they regularly list it as one of their top three corporate priorities. They simultaneously express unhappiness with the current state of their company’s talent. What do you think is coming between the positive intentions of CEOs and board members and the actual results of talent building in their companies?

BOYATZIS: Here’s the dilemma. Most CEOs, as well as executives, spend a lot of their waking hours thinking about metrics and specific goals—about financial analysis. It turns out all of that is very important and it activates a major network in the brain called the task positive network. You need that network to solve problems and make decisions.

There’s another major network in the brain called the default mode network. That network enables you to notice new ideas, be open to new ideas, be open to people, and think of what’s right in terms of moral decision making; not right-wrong, but what is fair and just.

The problem is these two networks suppress each other. We now have ample neurological evidence to show this. That means anytime you emphasize financial metrics, goals, and dashboards, you’re closing people down to being open to new ideas or seeing what’s happening in their market. You’re also closing them down to people and doing what’s right.

You need both of these networks, but on the whole, I would say it’s this huge, phenomenal power that financial metrics, goals, and dashboards have in organizations that has limited people’s perceptual, cognitive, and emotional abilities.

TALENT Q: A CEO comes to you and says, “Richard, you have seen many organizations, many problems, and many CEOs over your career. Based on the wisdom and learning you’ve gained over that time, distill for me the three things I absolutely must do to be a great CEO.” How would you respond?

BOYATZIS: I’d say first develop a shared vision—a shared sense of purpose. Be able to say, “Why do we exist, what’s our purpose, and why is it important that we’re here on Earth?” You’re not allowed to answer “shareholders” or anything to do with money. If you develop a shared vision with the people in your organization, you have a sustainable form of energy that’s far more powerful than any set of goals. Because it turns out that vision activates this default mode network.

The key is to understand how to use both the task positive and the default mode network. The antidote to the goals is vision. Every time you need to talk about a goal, make sure somewhere in that same hour you’ve talked about the purpose, vision, and customers.

Second, people have to feel you care about each other; they want to belong. We know the boomers were more purpose- and vision-oriented than the pre-boomers, the gen-Xers were more than the boomers, and the millennials are certainly more purpose-oriented and vision-oriented than the gen-Xers.

We have to appreciate that our entire workforce is thinking much more about “Why am I doing this?” and the purpose of the organization. That’s true even more than the amount of money as soon as you get up to professional or executive levels. So the second step is to build better relationships with the people around you.

You do that by developing people. That’s number three. People want to feel like they’re growing, and that comes about through development, whether it’s career pathing, job placement, task forces, or coaching and training. The more people feel their organization is committed to them, the more they’ll stay and give their all.

So one: Build a shared vision. Two: Build more resonant, better relationships. And three: Develop people in every way imaginable.

Marc Effron is the publisher of TalentQ, cofounder of the Talent Management Institute, and the president of The Talent Strategy Group, which helps the world’s largest and most successful corporations create incisive talent strategies and powerful talent-building processes. He’s also the author of 8 Steps to High Performance: Focus On What You Can Change (Ignore the Rest)