The research is clear: Unconscious bias isn’t holding women back. The smoking gun is the career path they took.

By Rob Kaiser and Wanda T. Wallace, Ph.D.

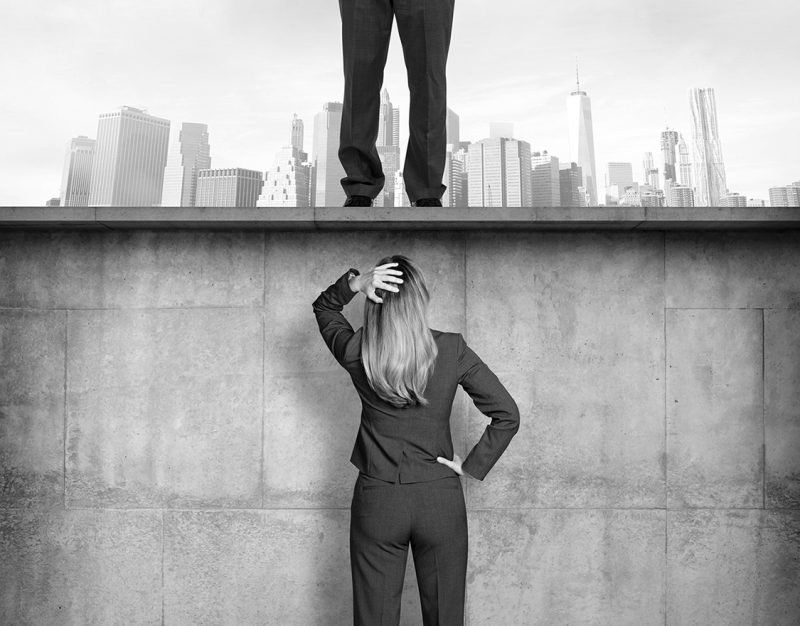

Diversifying the c-suite with more women is a top priority for many companies. But after 30-plus years chipping away at the glass ceiling, most people associated with this effort agree: There hasn’t been enough progress. The representation of women in corporate-officer roles in the S&P 500 has barely budged, with a mere 5 percent increase since 2000.

Why has gender equality in leadership been such a stubborn goal? The prime suspect is unconscious bias. Simply put, many believe the gatekeepers to higher office hold unconscious prejudices that make it hard to accept a woman in charge. This is next-generation discrimination, more insidious than blatant twentieth-century sexism, and it can infect even the most well intended.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Unconscious bias can take many forms, from cognitive shortcuts like “think manager, think male” to double standards (women have to be more competent than men to be seen as equally qualified) and the double bind (women are damned if they conform to the masculine idea and damned if they don’t).

Plenty of lab research demonstrates unconscious bias, but we believe it’s incomplete and perhaps even misleading as an explanation for gender imbalance in corporate leadership. Of course, we’re going against popular opinion, but we base our view on decades of research as well as experience coaching women executives and advising global companies. We are firm advocates for equality and have worked hard for it. But, quite simply, there’s more to the story.

Let’s start with research trends, which paint a picture of changing attitudes. A recent meta-analysis examined 99 studies and found that prior to 1982, men were usually seen as more effective leaders. But since then the gap has closed, and when there are differences, women are increasingly regarded as more effective. Though bias against women is routinely found in controlled experiments, there’s little conclusive evidence of pervasive bias against women among real corporate executives.

We published a study comparing 360 ratings for a matched sample of 857 pairs of upper-level women and men from seven companies. The study used two complementary and widely accepted methods for statistically identifying bias, and neither indicated the women were unfairly rated worse. In fact, there was some evidence of bias in favor of women: Females at the bottom of the performance distribution were rated disproportionately better than equally underperforming men. At the top of the performance distribution, women and men were rated the same. In other words, coworkers—both male and female, and across boss, peer, and subordinate perspectives—gave the lowest-performing women extra credit that they didn’t give to low-performing men.

These findings reflect a new reality: The corporate world has become more accepting of women in leadership. Most managers today are on board with the idea of equality. But greater support for having more women in leadership doesn’t mean that we necessarily have the mechanics figured out for getting them prepared for and into those roles.

So, if unconscious bias isn’t quietly operating in succession-planning discussions and denying women top jobs, what is? The smoking gun was most likely fired several years earlier, when young, aspiring female talent were offered, and took, career paths that were markedly different from the ones their male counterparts took to the top.

Myriad studies have shown that, compared to men, women don’t get as many broadening experiences that help cultivate strategic organizational leadership skills. In general, female talent gets far fewer cross-functional moves, international and expat assignments, line jobs, significant budget or P&L responsibilities, and access to mentors, female role models, and c-suite visibility.

Rather, they tend to land in tactical support roles implementing someone else’s vision and wind up getting stuck. There is a growing body of research showing that women score higher on such competencies as execution, planning, and results-orientation. The dark side, however, is a lower standing in strategic thinking, global perspective, and business acumen—the competencies required for senior leadership.

Make no mistake: This is a silent conspiracy, where everyone is complicit. Bosses will often make a capable woman their right-hand person—the reliable go-to who can get stuff done. HR has reinforced this with such prescriptions as “Play to employees’ strengths.” And women themselves repeatedly accept these assignments, perhaps preferring the safe and familiar. As one chief diversity and inclusion officer remarked to us, “The new double-bind is that high-potential women are getting rewarded for being tactical doers at the expense of becoming strategic thinkers.”

Compounding matters, aspiring women are not getting helpful feedback. Many managers are afraid of appearing sexist if they raise honest concerns about coming on too strong, micromanaging, or missing the big picture.

There comes a time when these dedicated and hard-working women expect a promotion into a big job. When they get denied, the most common knock: They aren’t strategic enough to lead across the enterprise. Most don’t see it coming and the shock is unsettling and disillusioning; it undermines trust in their managers and stirs questions about whether anyone cares about them. This is a major reason why so many mid- to late-career women leave their employer.

The solution requires everyone to take the long view. Run the numbers on how many women, compared to men, are getting assignments that provide broadening experiences—functional changes, cross-divisional moves, market-facing, expat, P&L, business development, and so on. The companies we advise find the ratio favors men about 5 to 1. To have any hope for parity at the top, HR must balance this equation early enough for high-potential women to accumulate these experiences.

Managers also have to muster the guts to have meaningful feedback and career conversations with aspiring women. This involves sharing the realities of what it takes to advance, including any concerns about a lack of strategic thinking or business acumen, as well as delicate topics like how their style may rub some people the wrong way. Managers also have to face the hard reality that what may be in a woman’s career interests might not be in the manager’s self-interest—perhaps moving to another function, division, region, or even company is what would be best for her.

Finally, there are things women themselves can do. First, ease up on the preoccupation with unconscious bias—what can you do about prejudice in someone else’s mind anyway? Instead, focus on managing your career with a priority on cultivating strategic organizational-leadership skills. Step out of the comfort zone and take risks that provide wider exposure. And network across boundaries; don’t always sit with the same old crowd at lunch. Branch out.

In addition, ask for projects and special assignments that offer visibility into how business strategy gets crafted and communicated. You may not always get what you ask for, but you probably won’t get what you don’t ask for. Also, learn to speak the language of strategy and frame comments in terms of alignment with company direction, positioning with different customer or consumer segments, outfoxing competitor moves, and making the business case. It is not enough to have a strategic mind; it has to be communicated to be recognized.

A Chinese proverb says that the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, and the second best time is now. The same is true with developing more high-potential women into strategic enterprise leaders. Grab a shovel and start digging.

Rob Kaiser is the president of Kaiser Leadership Solutions, which provides innovative tools, methods, and advisory services to help improve organizational performance through better leadership.

Wanda T. Wallace, Ph.D., managing partner of Leadership Forum LLC, coaches, facilitates, and speaks on improving leadership capability. She specializes in helping women (and men) get to the top and thrive, as well as helping managers build truly inclusive cultures. She is the author of You Can’t Know It All: Leading in the Age of Deep Expertise and the host of the weekly podcast/radio show Out of the Comfort Zone