As organizations must tackle more hot-button social issues every day, leaders are at greater risk than ever of saying too little. This is a problem, because feedback has never mattered more.

By Angela Lane and Sergey Gorbatov

How’s this for an understatement: Today’s business environment grows more complex by the minute. Thanks to the pandemic, uncertainty reigns and fear smolders.

In addition, populism, partisanship, and polarization has fully infiltrated not just governments and communities, but our organizations too. Social causes like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo have sidelined high-profile executives and public figures, and companies are now taking stands on racial inequality (Nike), immigration (Microsoft), and equal pay (BBC).

Working in such an environment means feedback has never been more essential, because feedback drives performance. Many organizations are at a loss for how to adequately handle feedback in the face of all these factors.

We’re not interested in these topics from a political standpoint. Instead, we want to focus solely on the impact of this new environment on organizational performance and answer the big question: How does this social pressure aggravate the chronic feedback deprivation in the workplace?

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Guarded Communication Harms Performance

Research shows performance improvement requires feedback, and feedback, to be useful, must be concise, clear, and candid.

But feedback is elusive. We crave it. We evade it. And we rarely give it. When we do give it, we most likely do it badly. Bad feedback doesn’t improve performance, and it may actually harm it, finds a meta-analysis in the journal Psychological Bulletin.

So how would an already vexed issue be impacted by an increasingly polarized social environment? If the broader ecosystem did have an effect, would it be to embolden employees and leaders alike to have tough conversations? Or, in this fragile environment, would we all be less willing to provide constructive criticism for fear of it being misunderstood at best?

To find out, we conducted a survey to better understand the role of external environment on performance feedback. Our early findings are both concerning and enlightening. The social environment does have implications for feedback. And in the view of more than 200 HR and business leaders we surveyed, you’re less likely than ever to hear the truth about your performance.

First things first: Feedback matters. There isn’t a debate around that. Ninety-three percent of respondents believe that feedback is either “very important” or “extremely important” in today’s work environment, with no practical difference between HR practitioners and business leaders.

In light of its importance, we asked about the likely implications for performance feedback. When asked for their assessment of the next 12 months:

• 35 percent of respondents said the level of feedback will increase.

• 20 percent said that business complexity would support increasing feedback despite the added challenges of the social environment.

• 15 percent responded that feedback would actually increase because of the social environment.

The majority of respondents believed that the quality or quantity of feedback, or both, would be affected by the prevailing social winds: Fifty-one percent say that while we’ll go through the motions of giving feedback with as much frequency as ever, the candor of that feedback will be reduced.

And that makes sense. A leader who was already dodging feedback because it’s uncomfortable, emotional, and risky to engage in an honest conversation now has yet another excuse not to give it.

Yet for those that believe in the value of fair, focused, and credible feedback as an indispensable tool in driving performance, these results must be alarming. Receiving inaccurate feedback may be worse than receiving no feedback at all.

HR Sees Feedback with Rose-Colored Glasses

Our second insight was about the difference between how HR sees the issues compared to other business leaders. The threat of a reduction in performance feedback could be okay if HR knew what to respond to, and how to respond. But HR sees it differently.

HR practitioners believe that feedback will happen with equal frequency, but it will be less candid. Based on assessment by business leaders, HR already significantly overestimates the extent to which feedback is given anyway. Eighty-one percent of HR respondents believe that managers give feedback to their employees once a week, while one-third of all business leaders surveyed said they never give feedback.

The implication is clear: HR likely underestimates its need to take a more overt leadership role in acting as an advocate for feedback to improve performance, despite challenging social conditions. So what does HR need to do to ensure that performance information flows freely? First, we must pinpoint the reasons why feedback doesn’t happen.

From a range of issues, all participants identified the fear of conflict as the single biggest issue preventing feedback. Again, not surprisingly, there’s a significant difference in how HR practitioners and business leaders view this. In our survey, 85 percent of HR respondents identified the fear of conflict as the major reason why feedback isn’t given, compared to 51 percent of non-HR leaders.

What concerns leaders more is their lack of experience in giving feedback. Sixty-five percent of business leaders identified this as one of their top three issues. Managers don’t believe they have the experience to navigate the feedback. While this could be a rationalization on behalf of leaders, the difference in their perspective, versus HR, is stark. Only 37 percent of HR practitioners believe a lack of experience lies at the heart of this problem.

Instead, HR is more likely to blame the lack of accountability for enabling an environment that won’t mandate for feedback regardless of external factors. Fifty-one percent of HR practitioners believe that there’s a lack of accountability. While this compares with only 29 percent for non-HR leaders, it appears they’re on to something.

When respondents answered a separate question on the consequences of not giving feedback, 40 percent said there weren’t any consequences at all.

The greatest negative repercussion for withholding feedback, meanwhile, could be that others will find out. Managers appear to be thinking, “Okay, I may have a reputation of someone who never gives feedback. But that fades in comparison with the emotional toll and time investment, and I will still get my bonus for the business results that I deliver.”

These findings suggest a path forward for HR that supports feedback despite an increasingly complex external environment. But before exploring potential practical actions, it’s helpful to analyze what isn’t on the minds of survey participants and bust some myths that might otherwise stop HR from acting.

With so much tension in the workplace, one might wonder if the threat of litigation stops leaders from giving feedback. Not so much: Not one business leader said this was a concern, while only 5 percent of HR representatives acknowledged it. Litigation, including union involvement, is not an impediment.

Neither, by the way, is internal politics. We believe organizational considerations are real. Complex reporting lines and structures only add to the challenge of human dynamics in an already complex environment. Managers do distort feedback for personal interests, according to 1987 research in what’s now called the Academy of Management Perspectives. But our findings indicate that politics isn’t a reason for leaders not to give performance feedback in the current environment.

Most importantly, it isn’t due to any belief that giving feedback doesn’t make a difference or can’t change performance. In our survey, there were only 12 percent of “non-believers” among the business leaders, and a mere 2 percent among HR partners.

The importance of feedback and its role in performance aren’t decreasing, so HR departments must respond to the risk of reduced candor and clarity between employees and leaders. But where to begin?

Most obviously, HR can respond directly to findings like ours. Leaders need experience. Leaders need support to practice and gain experience. Leaders believe that support will, beyond “training,” help build the skills needed to provide straightforward feedback in ways that motivate and develop.

And while experience, rather than training, would best address leaders’ needs, there may be a role for formal training within a larger system of support. Whether it’s opportunities to practice and gain experience or formal training, leaders feel they need to bring something to these developmental conversations. Leaders want to be able to offer support, but they feel unable to suggest appropriate development. This increases concerns about giving feedback with the necessary candor.

How to Create a Feedback Culture

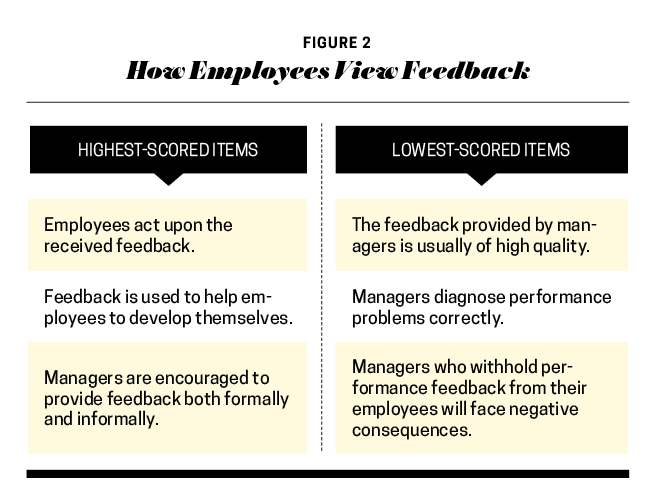

In our feedback culture assessment, respondents rated giving high-quality feedback, diagnosing the situation, and ensuring accountability as the three weakest elements.

But everyone agrees that a feedback culture will positively influence performance. The best HR leaders must respond by building a feedback culture that’s free of fear, where managers can do their job.

Where to begin? Start by ensuring an appropriate policy framework supported by simple, but rigorous processes that demand accountability. Make the rules painfully clear. In the absence of these foundations, HR won’t be able to deal with the lack of accountability, which makes it easier for leaders to avoid feedback—especially in a sensitive environment.

And if our survey data holds over bigger, more diverse groups, there is an accountability issue. Remember our finding that 33 percent of managers don’t give feedback at all? Interestingly, leaders, more than HR practitioners, feel there is accountability.

As we’ve noted, HR and business leaders report no consequences in their workplace. And where accountability does exist, the most significant consequence appears to be that others may potentially figure out that a particular leader doesn’t give feedback.

HR could think of this moment as an opportunity. Why not use the challenging external environment as a catalyst for discussions with leaders on what’s required to enable an environment where the feedback that matters is delivered?

Our research shows a high degree of variability between the responses of leaders and their professional HR partners. Knowing that leaders are less likely to be candid than HR can prompt a positive discussion on what the business needs to be okay, and the role of feedback in getting there.

Once triggered, this discussion can transcend our current moment. That would mean using these practical actions to potentially arise from a dialogue spurred by the current external environment and start building a culture of feedback. Beyond accountability, the hallmarks of a feedback culture that appear to be missing most frequently are providing quality feedback, based on accurate diagnosis.

HR is ideally placed to support leaders with both. HR partners have a unique position to influence both the individual feedback given and the collective capabilities built, which support a long-term feedback culture.

The easiest, most logical step in building a feedback culture is to make sure that employees act on the feedback provided and use it to develop and grow. These are the top-scored feedback culture indicators in our survey. The good news? Most respondents already have this system in place.

There’s also no shortage of encouragement of leaders to provide both formal and informal feedback. Unfortunately, that falls on deaf ears in environments devoid of accountability. This brings us to HR’s near-term focus.

You Must Motivate Leaders—and Hold Them Accountable

In this complex setting, HR must provide leaders with experience in giving feedback, and they should feel confident to hold those leaders accountable for delivery. The opportunity, beyond those practical “to-dos,” is to better understand the leaders’ dilemma and use the current moment as a catalyst to determine what it will take to build a culture of feedback.

The real problem is ignoring the risks and consequences of a culture of decreasing feedback. If the data is right, leaders will give feedback, but it will be less candid and more guarded than ever before. Employees need self-awareness to improve performance. In the absence of accurate feedback, performance is unlikely to improve. And if performance does change for the better, it was left to chance.

We know that a fraught social context causes people to avoid giving good feedback—even more than usual. But we also believe that good feedback is vital to the performance that’s critical to business success; giving feedback is a skill that can be both taught and learned; and when done well, feedback helps diffuse tensions by ignoring what isn’t relevant, focusing on what matters, and helping others to perform.

It’s this last point that should provide further encouragement to HR to trigger a bigger conversation on feedback in the current climate. Failure to be honest with employees has downstream effects on the employee’s growth and development, compensation, long-term outlook, and potentially job security. It also creates an unhealthy organizational climate where humanity is taken away from human relationships.

Not long ago, the tangible assets of a company equaled its value. Today, in many instances, the contribution of fixed assets is close to negligible. Instead, it’s the value of intangible assets that counts; 87 percent of the total valuation of companies within the Standard & Poor’s 500 is what we can’t see, according to Ocean Tomo research.

Peter Drucker predicted what we now know to be true: Innovation, creativity, and human performance provide the premium that the market rewards. A great share of that premium is available to today’s companies that decide to buck the trend and drive a culture of open communication and feedback.

It may be happening less, but it matters more. And it’s more valuable than ever.

About Our Research

The research cited in this story was conducted via an online survey between September and October 2018, targeting HR professionals and business leaders. These leaders were asked to provide their view on the impact of the broader social environment on performance feedback. A globally diverse group of more than 200 leaders responded, equally distributed between both genders and HR versus business leaders.

Angela Lane and Sergey Gorbatov work and write about the complex science of human performance while making it simple. Leveraging Fortune 500 experience gained across four continents, they equip leaders with practical tools for success. This article represents the authors’ personal opinions and not those of their employers.