Driving change amidst disruption is great in theory. But true agility isn’t about creating chaos—it’s about keeping things simple and stable.

By Elaine Pulakos, Ph.D.

Organizational agility and resilience have never been more important than they are today.

With disruptions from a global pandemic and changing technologies posing significant (even existential) threats, companies have been flattening their structures, integrating their functions, and training their leaders—all in pursuit of the agility they need to negotiate these challenges.

But our new research in more than 300 global companies has uncovered counterintuitive principles and practices that distinguish the most agile and resilient organizations.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

The Agile Organization

Agile companies do things differently than other organizations. They excel at devising new strategies that overcome threats, and they quickly jettison those that aren’t working. They engage in recovery planning, keep their cool, and bounce back quickly from jolts. And they’re frequently disruptors, rather than the disrupted.

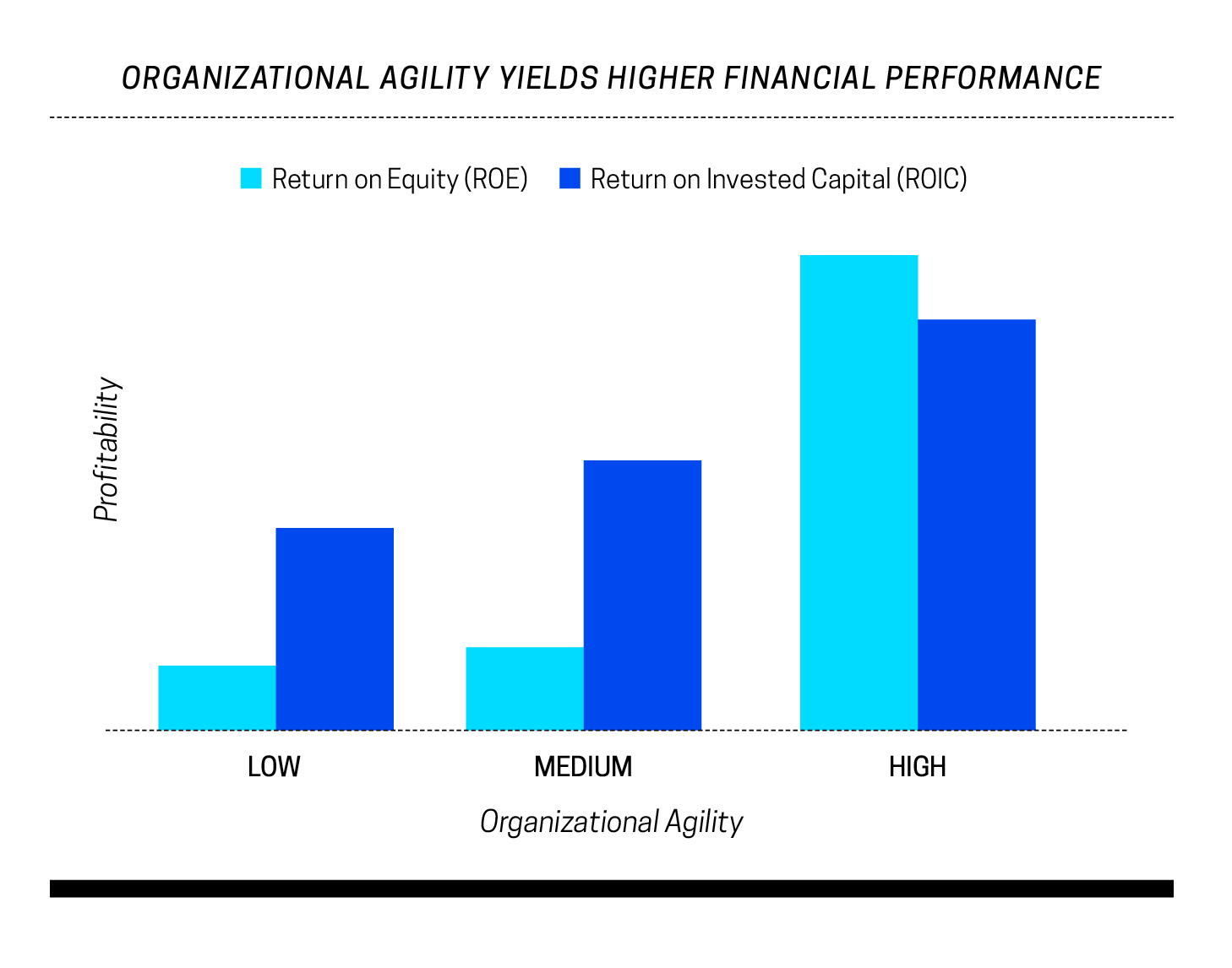

And agility pays. Companies that do these things best deliver remarkably higher corporate financial performance—for example, 150 percent higher return on invested capital and 500 percent higher return on equity.

But the active ingredients for creating organizational agility aren’t what you might think. They don’t focus on driving change, require complex multidisciplinary teamwork, or rely on personally agile people.

What separates the most agile companies from the rest is that they counterbalance the complexity and chaos of disruptive change with specific practices that yield simplicity, clarity, and focus. Like yin and yang, opposing but complementary processes form the nucleus of organizational agility.

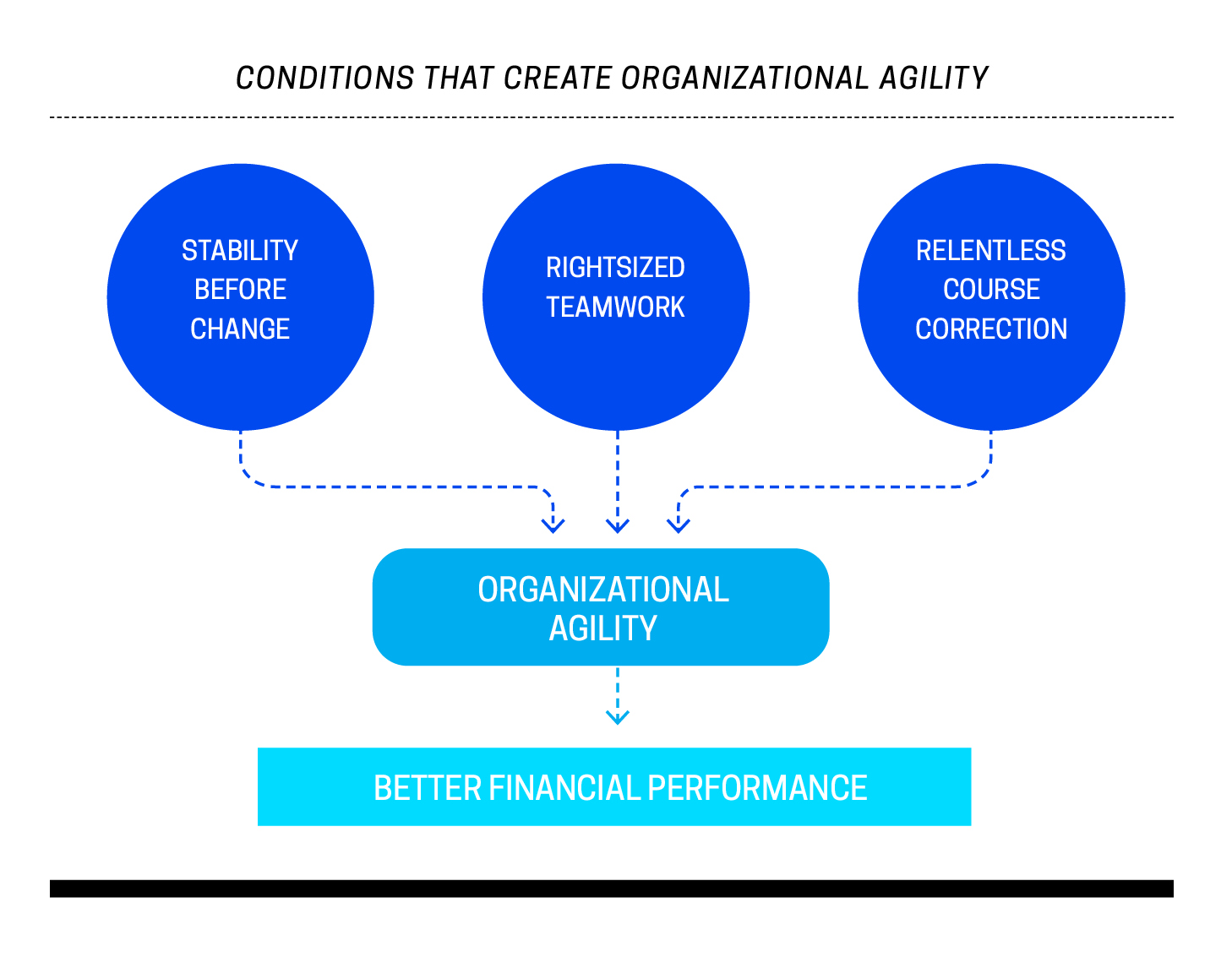

Of the several practices we investigated, there were three that separated truly agile organizations from the rest. Ironically, the most important one is building stability; the other two, only slightly less necessary, are rightsizing teamwork and relentless course-correction.

The Stability Imperative

Responding in an agile manner and recovering quickly from jolts requires a commitment to stability.

The logic is simple: Stability provides a solid foundation that reduces distraction, worry, and fear; this gives people the firm footing they need to collectively absorb change and recover quickly.

We identified seven practices common in the most agile companies that leaders can use to build stability.

Practice #1: Sharpen your focus. Disruptive change is distracting and causes people to worry about what’s going to happen next. Extreme disruptions can prompt irrational, counterproductive behavior.

When COVID-19 first hit, reactions ranged from downplaying the threat of a global pandemic, to frantic hoarding of critical supplies. Faced with disruption, leaders can stabilize the situation by clarifying what matters most and focusing their people on these vital few priorities. Consider putting “nice-to-have” initiatives on hold to give employees more space to tackle truly important challenges.

Practice #2: Break down barriers. Removing obstacles is stabilizing because it reduces the collective stress that comes with an inability to get things done. It’s important to stay attuned to what’s not working, help the team implement workarounds, and eliminate barriers to performance as quickly as possible.

A good recent example is when many companies shifted to virtual work almost overnight. There were countless problems from not having the systems needed in place to capacity overloads resulting from rapid acceleration of users. Leaders quickly implemented creative solutions to work around these barriers, such as meeting at off-hours or leveraging multiple virtual meeting platforms.

Practice #3: Optimize failure. Dealing with disruptive change requires solving unanticipated problems, small and large. Solutions won’t be perfect out of the box. It’s important to avoid finger-pointing and blame when things don’t go as planned; instead, use failure as a teachable moment, harvesting lessons to further refine the team’s approach.

Practice #4: Build optimism. Leaders need to project confidence, strength, and positivity when things get turned upside down.

This doesn’t mean denying reality or sugarcoating bad news, which only breeds cynicism and distrust. The key is acknowledging setbacks and disappointments, and then focusing—optimistically but realistically—on what needs to be done to move forward successfully.

Practice #5: Reassure your people. It’s important to put the minds of people at ease by affirming their roles, value, and future.

But this, too, must be realistic; be careful not to overpromise. Focusing on concrete, positive information—about the company’s health, survival strategies, and plans to protect employees during change—can have strong stabilizing effects.

It’s also important to be transparent about difficult news, such as cuts, and explain why they’re needed. Tough news delivered properly and in a timely fashion can be stabilizing, while misleading or insufficient communication can leave people assuming the worst.

Rule of thumb: Check in with people before you check on them. For example, ask how they’re doing and let them know you care before turning to work. As a leader, you don’t have to solve every practical or emotional problem. You just need to listen with empathy and provide emotional support.

Practice #6: Harmonize your resources. Having too few resources creates instability, so it’s important to balance work demands with resources.

Companies have been operating with a do-more-with-less mentality in general, and disruption often prompts further belt-tightening. Smart leaders think through the impact of cuts on their already-stressed employees.

Rather than implementing reductions too quickly, they pause and think creatively about how to reduce demands or leverage available resources differently to achieve a balance that’s stabilizing.

Practice #7: Plan for recovery. Engaging in preemptive recovery planning is stabilizing because it boosts confidence that teams can absorb jolts.

Even if these scenarios don’t play out, the act of planning for contingencies shows team members they can handle the unexpected, which helps them respond in a more agile manner when necessary.

Recovery planning during disruption gives employees a positive focus and allows tracking progress; this has a psychologically stabilizing impact.

Right-Size Teamwork

To combat disruptive change and competitive pressures, companies have been embracing teamwork. The theory is that teams of people with different skill sets and backgrounds enable agility, innovation, and better outcomes.

However, the reality that companies are experiencing—and research is starting to confirm—is that bringing together a bunch of people with diverse expertise often stalls rather than fuels innovation, especially early on.

Teamwork can introduce complexity, communication disconnects, and tensions that lead to counterproductive behavior such as jockeying for position, making power grabs, and protecting one’s turf. The idea that companies should drive teamwork needs to be balanced by an awareness of the challenges of teamwork in creating an agile organization.

Consistent with these ideas, our research found that the most agile and financially successful companies don’t maximize teamwork; rather, they right-size it. This entails defining what type of teamwork—and how much of it—is needed to perform work most efficiently and effectively. It requires judiciously including the right mix of people who can contribute at the right times in order to avoid overdoing it.

Thinking about your teamwork requirements in terms of four broad categories will help to prevent teamwork overload.

1. Sometimes teamwork is nothing more than a hand off. Work is mostly independent, but at certain points, one person needs to pass along information or resources to others. This requires clear communication and coordination, so everyone understands what’s needed and when, but otherwise, it brings no teamwork requirements.

2. Synchronized teamwork is needed when two or more separate teams (or individual contributors) perform the same routine independently, but must remain in sync. In a regional sales team, for example, each person prospects, closes, and manages different customers using the same process, and the sum of everyone’s work determines the regional team’s success.

3. Coordinated teamwork is required when people perform independent roles that impact each other. An example is medical teams that consist of different specialists—physicians, pharmacists, dietitians, respiratory therapists, and nurses—who each perform distinct tasks to achieve a team outcome.

4. Some work requires truly interdependent teamwork, which is the most complex form of teamwork. For example, figuring out how to bring new products to market requires different skills working together. As work takes shape and solidifies, roles and responsibilities can change as members work through unpredictable situations and make decisions.

Sometimes a team’s work fits neatly into one of these categories. However, the teamwork requirements can also change with different phases of a project, so they need to be monitored and adjusted.

Right-sizing teamwork is an exercise in simplifying. The idea is to critically evaluate whether teamwork is actually needed and when, determine what type of teamwork is required, and boldly cut out extraneous people and process.

Thinking in terms of the four teamwork categories will help leaders and team members align on their requirements. The reduced complexity and ease of getting work done that results from rightsizing teamwork makes it possible to avoid the process loss incurred by overdoing it, thereby allowing organizational systems to respond with higher agility and resilience.

Relentless Course-Correction

Relentless course-correction is accomplished through a shared mindset and specific activities that build agility by rapidly diagnosing and addressing performance issues. It requires a climate in which people welcome consistently raising the bar and aren’t afraid to call out problems, rapidly diagnose them, and eliminate them.

The hardest part of this practice is overcoming people’s fears about candid communication and feedback. These fears have their origins in the unproductive ways that people in organizations have learned to address performance issues.

When something goes wrong, our first instinct is to decide who’s to blame, rather than simply solving the problem. Finger-pointing personalizes performance issues and triggers automatic defensive reactions because people feel attacked and threatened.

Most people, even leaders, don’t want to incite these reactions in others, and this contributes to collective avoidance of performance issues. The problem when people look the other way, however, is that the issues often fester and grow.

Talking openly and regularly about the psychological and social barriers that cause finger-pointing, defensiveness, and fear can help neutralize these reactions, but specific methods and tools are also needed to help people get over their natural tendencies to avoid performance issues. Our research found two particularly useful ways to accomplish this.

1. Use objective performance metrics. Everyone does better when they can track their performance in real time. For example, getting feedback throughout a project is better than waiting until the end to learn there were issues you could have handled easily early on.

Performance tracking helps inoculate people from fear of raising issues by regularly showing both hits and misses. With data telling the story, there’s less need for people to raise the issues, less worry about repercussions, and less debate about whether a problem exists.

2. Implement methods to identify and address performance issues. Humans are preprogrammed to jump to conclusions based on their assumptions and biases. These help people process large amounts of information quickly; however, they often lead to convenient, but incomplete conclusions.

People make better judgments if they set aside these shortcuts and slow down their thinking to thoroughly analyze situations and consider alternatives. Structured methods, such as Six Sigma’s “5 Whys,” help teams diagnose root causes.

This method asks why a problem is happening and uses the answer to ask why again, until the root causes are identified. This technique can become a well-established and effective practice when teams repeatedly use it and leaders consistently encourage it.

Your Mission: Become a Truly Agile Organization

In the wake of current disruptions, companies have been focused on driving change, doing more with less, and maximizing teamwork—things that may, ironically, undermine agility more than cultivate it.

These aren’t necessarily bad things to do. But when mindlessly applied, they can be overdone, which adds complexity, inefficiency, and frustration to the constantly changing, intensely competitive situations companies are facing today.

Our research shows that agility—a key to competitive success and superior financial performance—is best achieved by offsetting the chaos and complexity of disruptive change with three key practices that simplify work, clarify what matters most, and focus squarely on driving high performance: creating stability, rightsizing teamwork, and relentlessly course-correcting.

Elaine Pulakos, Ph.D. is CEO of PDRI and an expert in building organizational and team capabilities that translate into business growth. She is well-known for her research and writing on agility and resilience and has extensive global experience helping companies build these capabilities to increase their competitive advantage and performance.

Further Reading

Pulakos, E. D., Kantrowitz, T., & Schneider, B. (2019). What leads to organizational agility: It’s not what you think. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 71(4), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000150

Pulakos, E. D., & Kaiser, R. B. (2020). To Build an Agile Team, Commit to Organizational Stability. Harvard Business Review, April 07, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/04/to-build-an-agile-team-commit-to-organizational-stability

Pulakos, E. D., & Kaiser, R. B. (2020). Don’t Let Teamwork Get in the Way of Agility. Harvard Business Review, May 12, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/05/dont-let-teamwork-get-in-the-way-of-agility