How do you boost employee sentiment? By satisfying each team member’s three personal needs: believing, becoming, and belonging. Lead the way and your organization will soar.

By Dave Ulrich

It was J.B. Ritchie, the professor who introduced me to organization behavior and subsequently became a lifelong mentor, who once told me, “Organizations don’t think—people do.” The phrase sparked my imagination and career. I’ve spent my professional life examining how organizations shape people’s lives, and how people deliver organization outcomes.

These personal passions and professional interests are captured in the field of study broadly called talent, which has of course become an industry of ideas with impact. Scholars work to define talent. Consultants turn talent ideas into tools. Business leaders and HR professionals adapt those tools to deliver value to how people think and act in organizations. So what comes next?

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

To answer that question, we must first answer two others: First, what is the evolution of how we think about talent, particularly around employee sentiment? Second, how can leaders better use talent insights to improve personal and organization outcomes?

Neither has an easy answer. But by exploring both, we can begin to imagine future talent frameworks and actions. Let’s start by getting sentimental.

The Evolution of Employee Sentiment

Over the past 50 years, there have been thousands of attempts to define talent. But the simplest typology of talent includes both competence and commitment.

Competence deals with the knowledge, skill, and ability of employees. Increasingly, competence includes not only employees, but technology-enabled systems, like robots and artificial intelligence. Competence also includes full-time employees as well as contingent or gig workers. Employee competence has spawned innovations in how to bring people into the organization (setting standards, sourcing talent, securing talent, orienting talent), to how to move people through the organization (career planning, training, managing performance), and to how to retain and remove the right people. While there have been plenty of new insights in these areas, the greater talent challenge is often about ensuring employee commitment.

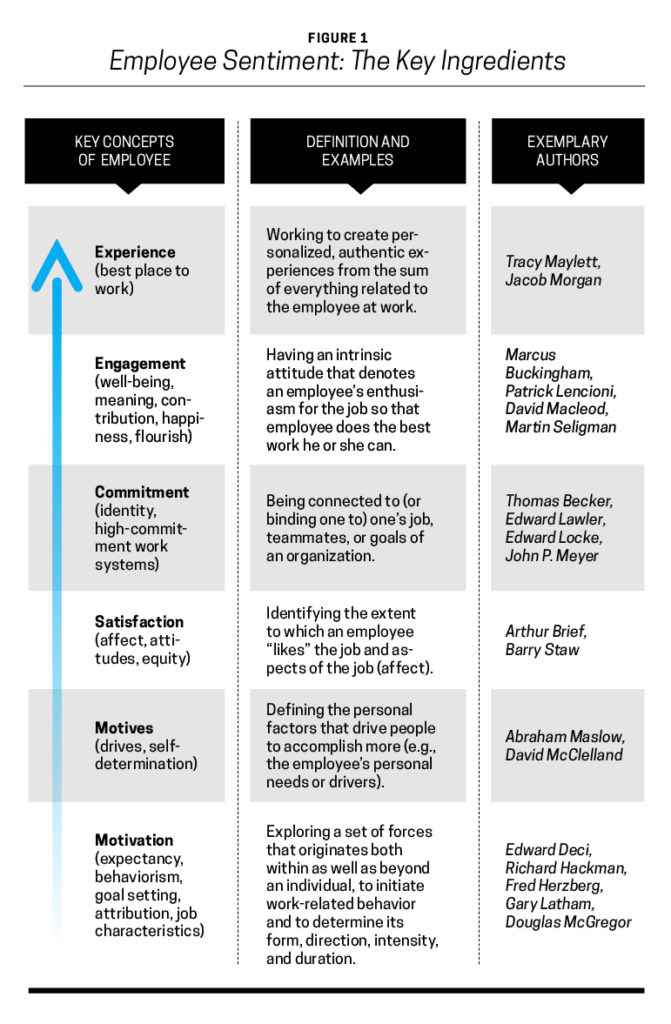

Commitment is about ensuring that competent employees allocate their discretionary energy (broadly called employee sentiment) to accomplishing work outcomes. See Figure 1 for a brief summary of some of the key topics in managing employee sentiment.

Why this cursory and brief historical overview? First, the study of employee sentiment isn’t a new topic. Generations of organization scholars have worked to inform organization leaders on how to inspire and fully engage their people. Second, too often, efforts to improve talent fail to respect and build on previous work and thus reinvent and reinforce what others have done. Without building on previous work, “new” insights are like old wine in new bottles—revisiting old ideas with new terms and not really making progress. And it’s just plain helpful to understand the past so that we can discover new ways to help employees give their best efforts at work.

The legacy of approaches to talent sentiment in Figure 1 help capture emerging themes of the past that may frame approaches for future talent management. The future of talent in organizations is also shaped by the key trends, including social and global diversity, rapid technological change, industry transformations, political dynamism, social responsibility, and demographic shifts.

These trends give employees increased choice and flexibility about where, when, and how they work; encourage relatively simple typologies that quickly capture employee attention; and redefine what organizations offer individuals to increase their sentiment.

Based on the past and responding to the future, organizations give employees a sense of:

- Believing: An employee finds personal meaning from the organization because he realizes his personal values derive from and align with the organization’s purpose and values.

- Becoming: An employee learns and grows through participation in the organization because it enables her to pursue new talents through opportunities.

- Belonging: An employee has a personal identity and develops new relationships because the organization puts employees in contact with one another.

By meeting these three personal needs, organizations can increase employee sentiment, which delivers value to customers and investors.

So how can you, as a leader, start to play your part?

I. Believing

Our search for meaning isn’t new. The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl’s landmark 1959 book, Man’s Search for Meaning, for example, explored his quest for meaning during his time in Nazi concentration camps. But in recent years, as this search has become very important for employee sentiment, the need for meaning has been characterized in a 3-step logic:

Step 1 is happiness found from activity (what is done); step 2 is experience (how it is done); and step 3 is meaning (why it is done).

This 3-step process draws on insightful work from positive psychology (including research by Martin Seligman, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, and Sonja Lyubomirsky) to describe how people respond to stimuli:

- Activity: Be motivated by pleasure.

- Experience: Get into the flow of an activity.

- Meaning: Find a personal purpose from the activity.

The more you understand this logic, the more you can reframe the impact of many of life’s events. Here are three examples:

EATING AND FOOD

- Activity: Eat food (vending machines, fast food, or quickie breakfast).

- Experience: Have a meal (restaurant experience with good service; fancy meal).

- Meaning: Have a meal with family and friends, use a meal to celebrate a significant event (Thanksgiving, Ramadan, a birthday or anniversary).

SHOPPING

- Activity: Buy a product (online or in-store).

- Experience: Have a great shopping experience (online by companies anticipating your needs; in-store by employee service).

- Meaning: Find personal value from the shopping experience (you look or feel better because of what you bought).

MUSIC

Activity: Listen to a song (often on your playlist with headphones).

Experience: Attend a concert to sense the artist and followers.

Meaning: Have the music remind you of something that matters in your life. (My wife and I, for example, had “our” music artist, Nana Mouskouri. We attended her concert, which reminded us of our younger affections.

This 3-step evolution shapes how we respond to our world, evolving from what we do to how we do it to why we do it. In all of these cases, meaning matters and moves beyond simple engagement to real contribution. In regards to talent, the same three steps apply:

• Activity: Help employees feel satisfied.

• Experience: Build employee commitment or engagement.

• Meaning: Inspire employees sustain a personal commitment through taking ownership of their work and finding real meaning from it.

When employees find meaning in their work, they experience increased personal well-being, self-confidence, physical health, and personal productivity.

For example, top new entrants in the workforce often differentiate potential employers by the organization’s social responsibility. Organizations that give back through products, services, philanthropy, and other means often attract and retain the best employees. This social commitment shows up in a “triple bottom line” of profit, people, and planet. And investors pay increasing attention to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. Leaders who include beliefs and values as part of their business message will create more meaning for employees.

How to Put Believing into Practice

Leaders make believing practical to employees by becoming meaning makers. They help employees connect their personal values to the organizational values. Here are three starting points.

1. Create a purposeful organization. As meaning makers, leaders help define a broader purpose for their organization. The organization isn’t just a bundle of activities (step 1) or processes (step 2), but a deeper meaning often connected to a deeper sense of values. Southwest Airlines, for example, strives to democratize the skies with cheap fares. Google aims to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Unilever has a purpose of “making sustainable living commonplace” with goals around improving the health and well-being of all people while reducing environmental impact.

2. Help employees become clear about their personal beliefs. Meaning makers also help employees answer personal questions like: What do you want to be known and remembered for? What do you want to contribute through your work? What problems do you see that you’d like to help with? These questions help the employee recognize his or her personal brand and identity.

3. Connect organizational purpose with employee beliefs. Leaders help employees recognize that their personal identity will be enhanced through their active participation in the organization. Southwest, Google, and Unilever attempt to hire people whose personal beliefs align with the organizational purpose. This alignment enables employees to find more meaning at work, and thus more personal well-being and productivity. For example, Southwest has the highest pilot productivity in the airline industry.

II. Becoming

Good people want to become better, and organizations are a unique setting for personal development. By giving employees opportunities for stretch assignments, training, and new projects, employees learn and become better. When employees learn and grow in their work setting, they find more personal meaning.

A number of ideas (learning agility, resilience, perseverance, and grit) coalesce around the principle of becoming better. Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck’s growth mindset concept captures the essence of becoming. In her research, she differentiates between a fixed and growth mindset, as shown in Figure 2.

Creating a growth mindset affects how individuals become better at work and at home. We often ask participants in workshops to think of a time when they failed at something and to remember the angst and feelings of loss. Then, we ask them to share what they learned from that experience, which often yields remarkable insights. The participants tell us that the lessons they learned from hard times were some of the most important in their personal growth.

Growth mindset in organizations often comes from deactivating threats, approaching values, and connecting to people. Neuroleadership pioneer David Rock identified five potential threats at work: status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness (SCARF). When any of these feels threatened, the brain shuts down and is not be open to growth. But by neutralizing these threats, employees are more open to learning and finding meaning and purpose from work.

How to Put Becoming into Practice

Leaders help employees become better by becoming growth leaders. Follow these steps to help your employees learn and your organization grow:

1. Focus on learning. Both individuals and organizations learn when they experiment, practice continuous improvement, seek next practice, and take risks. Learning often comes after seeming failures where insights are gleaned and transferred to the next setting. When leaders can avoid blame, punishment, and shame, they can often turn failure into learning by asking questions like:

• What was hard today? How did you stick with it?

• What bugged you today? How did you get around it?

• What problem came up today? How did you try to solve it?

• What did you experiment with today?

• What did you learn from trying it?

Growth leaders become better not by failing, but by learning.

2. Praise risk and improve the process. It’s easy for a leader to praise the outcome of a project (“You exceeded customer expectations”). But an exclusive outcome focus doesn’t encourage becoming better. Growth leaders explore the process (“How did you exceed expectations?”), then generalize those lessons to the next experience. Dreams don’t work unless you do.

3. Tell resilience stories. In the wake of 9/11, researchers found that children who knew stories of the family and ancestors were more resilient. Likewise, employees who know stories about company history, exceptional customer service, or product efficacy will be more resilient, hardy, and able to become better. Growth leaders create narratives that inspire resilience.

4. Scan for positives. Not all criticism is bad—especially when it’s used to get employees thinking about the positives that they can build on. Growth leaders ask positive questions like:

• What was a happy surprise today?

• How did you or others help it happen?

• What are three things you were grateful for today? How did you savor them?

• What was hard today? How did you stick with it?

• What problem came up today? How did you try to solve it?

These questions encourage what is right more than what is wrong.

III. Belonging

Belonging (being connected, joining a community, having a high-relating team) overcomes loneliness (social isolation) and predicts employee sentiment. The U.S. Surgeon General recently stated that loneliness is a more serious health problem than opiates. In fact, last year, the U.K. named a Minister of Loneliness to create policies to deal with the challenge of social isolation.

Loneliness (social isolation) affects all age groups. British research found that 200,000 older people haven’t had a conversation with a friend or relative in more than a month.

For the younger, digital-native generation, technology often leads to superficial connections. It’s relatively easy to “unfriend” someone, and Instagram and Snapchat generally depict people doing happy and positive things, which only makes the viewer feel more lonely in comparison. Those who spend more than 2 hours a day on social media feel more social isolation.

Belonging draws on attachment theory, which essentially states that when someone has strong emotional attachment to another (person or organization), their personal well-being increases. This improved well-being in turn boosts personal productivity and overall organizational performance. Belonging requires work to invest in relationships, using technology to connect and not contact, empathy between people one on one, and personal accountability for discovering relationships that matter. Belonging is active, not passive; requires persistent work; endures over time; is tied to shared values; and shapes well-being.

How to Put Belonging into Practice

Leaders create connection when they help their employees feel a sense of belonging. These community leaders help employees work better together as team or organizational citizens. You can be a community leader if you do the following:

1, Recognize that belonging requires work. C.S. Lewis, the famous religious author, characterized hell as a place where people who disagreed moved away from each other. Over time, everyone lived in moated and gated mansions far away from everyone else.

Belonging requires the hard work of investing in a relationship. One leader had a morning staff call for 15 minutes every day no matter where the employees were in the world. One of the reasons for this call was to update business issues, but more importantly, to form a team where people felt that they belonged. Community leaders foster belonging by being able to disagree without being disagreeable, have tension without contention, and move from divergence to convergence and back again without personal enmity. Conflict becomes an opportunity to strengthen relationships.

2. Use technology to build connections, not contacts. Technology makes the world a global village, but it’s often one of increasingly isolated people. Like walking down the street of a large city, there are literally crowds of people, with each person moving with purpose and direction. But crowds don’t necessarily lead to belonging. Technology dramatically increases breath of contacts, but not necessarily depth.

Counting likes and followers or joining a group doesn’t imply belonging. Community leaders can use technology to connect if they personalize their use of technology. Instead of sharing scripted studio posts, one leader became more authentic by creating short weekly posts about his focus, priorities, and experiences. Another leader asks colleagues to share positive experiences with an employee through technology on that employee’s birthday. This affirming exercise helps employees feel closer with their colleagues.

3. Demonstrate empathy. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has a new leadership mantra about empathy, which means understanding and feeling what others experience. He claims that empathic leadership leads to connection, which leads to innovation, which leads to better business performance. Community leaders build empathy in their professional relationships by asking how people are doing, being aware of personal circumstances, and being willing to help others.

One leader began his regular meetings with a brief personal interlude: “Who has a good news moment to share?” One sends personal handwritten gratitude notes to employees. Another frequently asks herself, “How can I be helpful?” These empathic actions create a sense of personal belonging between leaders and employees.

4. Ensure that employees take personal responsibility for finding meaning. Agency theory has changed how investors invest. When an agent acts on behalf of the owner, the agent often sub-optimizes decisions. Investors want managers who aren’t just agents, but active participants in investment decisions, ergo the rise of equity-based compensation, private equity, and other mechanisms to make managers into owners and not agents.

Community leaders create belonging by asking employees what they think and encouraging them to take ownership of innovation and personal work. Employees shift from being passive agents to active participants in organization actions.

In employee engagement, this changes questions from, “Do I like my pay, boss, or working conditions?” to, “Do I do my best to earn my pay, build a relationship with my boss, or improve working conditions?” Marshall Goldsmith calls this active engagement, and it shifts the responsibility for belonging from the organization to the individual.

J.B. Ritchie, my mentor, was right: Organizations don’t think—people do. So how do we shape how people think, act, and in turn shape organizations? There’s little question that talent shapes an organization’s results more today than ever before. Understanding and managing talent is an ever-growing field of inquiry that will help individual employees experience personal well-being and productivity, and organizations deliver value to customers and investors.

Rather than rediscover previous principles, it’s helpful to move forward in upgrading talent. A primary agenda for talent is improving employee sentiment through shaping how employees find meaning at work through shared beliefs, helping employees become better through a growth mindset and learning, and finding a sense of belonging through creating a community. These principles define new roles for leaders, meaning makers, growth sponsors, and community builders.

Through believing, becoming, and belonging, scholars, consultants, and business leaders can help people shape organizations that have a profound impact on society.

Dave Ulrich is the Rensis Likert Professor at the Ross School of Business at University of Michigan and a partner at The RBL Group, a consulting firm focused on helping organizations and leaders deliver value. He studies how organizations build capabilities of leadership, speed, learning, accountability, and talent through leveraging human resources. He has helped generate award-winning databases that assess alignment between strategies, organization capabilities, HR practices, HR competencies, and customer and investor results.