Proponents of this principle say people can improve if they just believe. But it’s time to separate positive intention from scientific proof.

By Marc Effron

During a recent podcast interview, the interviewer called out the chapter in my book 8 Steps to High Performance, where I say a growth mindset isn’t proven to work. “I was hurt by that section,” he said, “because having a growth mindset has had a very positive effect on my life.”

That interaction perfectly highlights the problem with the concept of growth mindset. Did the interviewer mean he always believed he could change and grow, and therefore he was successful? Did he mean he believed in his ability to become more intelligent, and therefore did become more intelligent? Was he saying he was resilient when going through challenges? Was he saying he had often been successful when he tried hard? Was he saying he had a positive attitude in life, and it had served him well?

Regardless of what he meant, could he really be sure a growth mindset had a positive effect on his life? Or were the positive effects he attributed to having a growth mindset really due to other factors? He’s an intelligent individual, and intelligence is the largest predictor of our success in life and work.[1]

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Or perhaps the benefits he noticed were due to his personality traits that naturally predisposed him to work hard and be resilient.[2] That brief conversation raises the two most important questions about the concept of growth mindset: What do those words mean? And does growth mindset actually matter?

What Exactly Is a Growth Mindset?

If you believe growth mindset means if you try harder, you can accomplish more, you can stop reading when you finish this section. We agree, and the science—in areas from self-efficacy[3] to goal setting[4] to motivation[5]—supports that exerting more effort often leads to better results.

That age-old belief also appears everywhere from the Bible[6] to Buddha[7] to Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking[8] to the children’s book The Little Engine That Could[9].

If that’s how you’re defining the concept, let’s stop using the term “growth mindset” and call it “trying hard” or “having a positive attitude.”

However, if you believe a growth mindset means different outcomes in life will occur if someone has a fixed mindset or a growth mindset, or that it’s possible to increase one’s intelligence or change one’s personality, please keep reading.

The term “growth mindset” is used very casually by leaders, consultants, and the media, so let’s start with the author’s original definition. Growth mindset creator Carol Dweck defines it in her book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, as “the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your efforts, strategies and help from others.”[10]

She describes it in a Harvard Business Review article as, “Individuals who believe their talents can be developed (through hard work, good strategies, and input from others) have a growth mindset.”[11] She states it even more boldly in a recent article, as “students who believed their intelligence could be developed (a growth mindset) outperformed those who believed their intelligence was fixed (a fixed mindset).”[12]

Dweck claims the consequences of having a growth mindset include higher achievement in academic situations at a minimum and, through numerous stories in her book, suggests a growth mindset can lead to success in any endeavor in life. Her overall theme: You can achieve superior results if you believe intelligence and personality can be changed. As evidence, her book is filled with stories of people who had a setback (i.e. failed their first photography course) and then later had a success (became a well-known photographer).

Dweck defines the opposite of having a growth mindset as having a fixed mindset. She describes this as “believing that your qualities are carved in stone”[13] or “those who believe their talents are innate gifts.”[14] In Mindset, she describes those with a fixed mindset as “fragile” and the consequences of it as, “The fixed mindset limits achievement. It fills people’s minds with interfering thoughts, it makes effort disagreeable and it leads to inferior learning strategies. What’s more, it makes other people into judges instead of allies.”

An organization’s mindset matters, too, according to Dweck. “When entire companies embrace a growth mindset, their employees report feeling far more empowered and committed; they also receive far greater organizational support for collaboration and innovation. In contrast, people at primarily fixed-mindset companies report more of only one thing: cheating and deception among employees, presumably to gain an advantage in the talent race.” Dweck presents no evidence to support those claims.

Is There a Problem Here? And Is Growth Mindset the Solution?

Before we discuss if growth mindset solves a problem, we should ask if there’s a problem that needs to be solved. There’s no research about the percentage of people who have a growth or fixed mindset (and no validated way to measure either of those states). Dweck says 40 percent of students have a fixed mindset, but also says everyone is a mix of fixed and growth mindsets and that “a ‘pure’ growth mindset doesn’t exist.”[15]

So even the concept’s creator can’t say whether 1 percent or 99 percent of the general population has a fixed mindset that needs to be changed.

There’s also no science that shows how easy or difficult it is to change one’s mindset from fixed to growth. Can it be changed as easily as telling a colleague, “I’m sure you’ll do a great job”? Can it be changed by redesigning a job so someone gets more positive reinforcement? Can it be changed through better incentives? Or perhaps it can be changed with a proverbial, motivational kick in the rear?

This leaves us wondering. If we don’t see an obvious problem and we don’t know if other solutions would be more effective if there is a problem, is growth mindset just a solution looking for a problem?

Does Growth Mindset Work?

The most important question, and one that few growth mindset supporters ask, is “Does growth mindset work?” If there are such things as a fixed mindset and a growth mindset, is there any scientifically proven benefit in having one mindset or the other, or in moving from fixed to growth? You can decide for yourself based on the facts, which include the following:

• Multiple scientific attempts have failed to replicate Dweck’s and others’ claims about the impact of growth mindset.[16][17]

• A recent study reported on three failed attempts to prove growth mindset works and found lower academic performance for a small portion of the population studied.[18]

• A recent experiment comprehensively tested the claims of growth mindset and found they were not supported. The largest correlation the researchers found was in the opposite direction predicted by growth mindset advocates. In that case, “fixed mindset” students performed better after getting negative feedback on a test.[19]

• A 2018 meta-analysis found extremely small effects from growth mindset interventions.[20]

• Dweck and her coauthors’ 2007 research has been criticized for reporting results that do not meet typical standards of statistical significance.[21] [22] Another one of her recent articles[23] has been strongly criticized by statistics professors for questionable statistical analysis, with one saying that “They’re using statistical methods that are known to be biased . . . they’re using statistical methods that will allow them to find success no matter what.”

• A recent comprehensive study on growth mindset showed a growth mindset intervention having no effect on the vast majority of students and a minuscule positive effect (0.1 grade points) on a group of low-achieving students.[24]

• There’s no science that shows a growth mindset will make someone a higher performer at work. A meta-analysis of “goal orientation”—a concept related to growth mindset—found no positive effects in work settings.[25]

• A rare study that included growth mindset in the workplace (but didn’t directly measure its effect) showed it was leaders with fixed mindsets who had meaningfully higher engagement, and the largest improvement in engagement was due to people trying harder, not to having a growth mindset.[26]

Frothy media articles about companies like Microsoft claiming growth mindset drives higher work performance present no research to support their claims.[27] When Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella talks about growth mindset, he makes the same mistake described earlier and talks colloquially about growth mindset as being about “attitude.”

Certainly attitude can drive effort, but that isn’t related to growth mindset; that’s grounded in established science around engagement and motivation. The company’s recent recovery can most reasonably be attributed to its executives making smarter choices about Microsoft’s products and services.

Actually, It Would Be Strange If Growth Mindset Did Work …

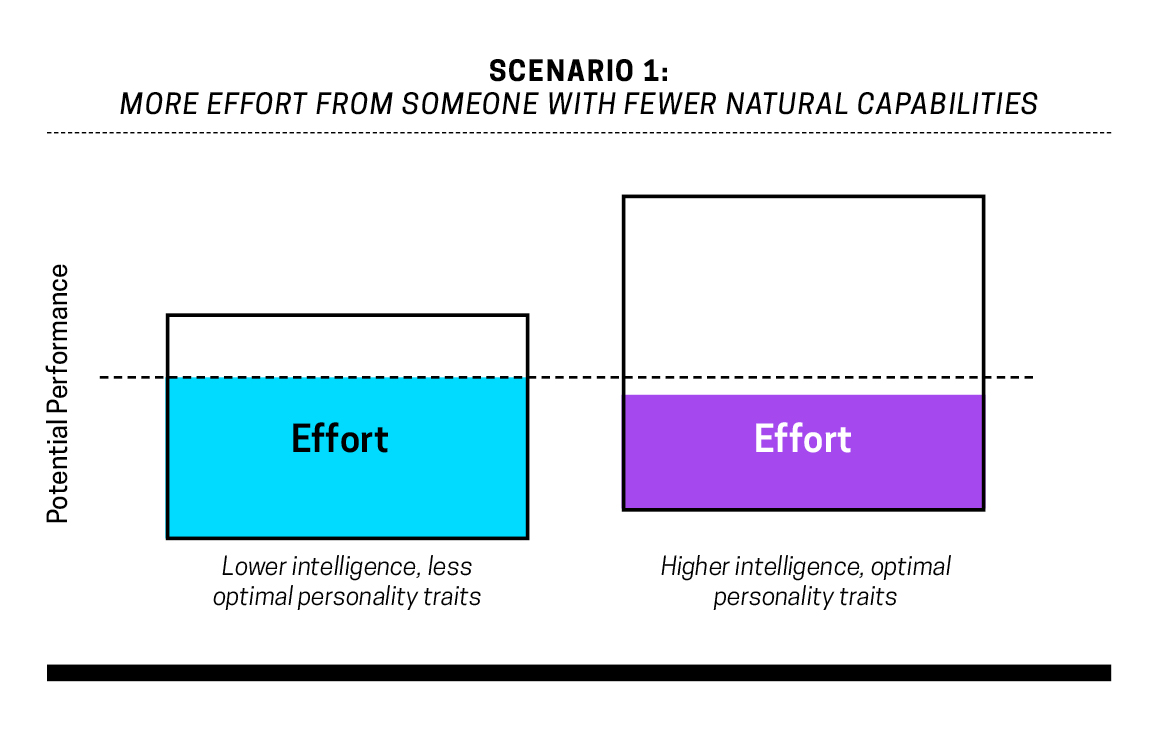

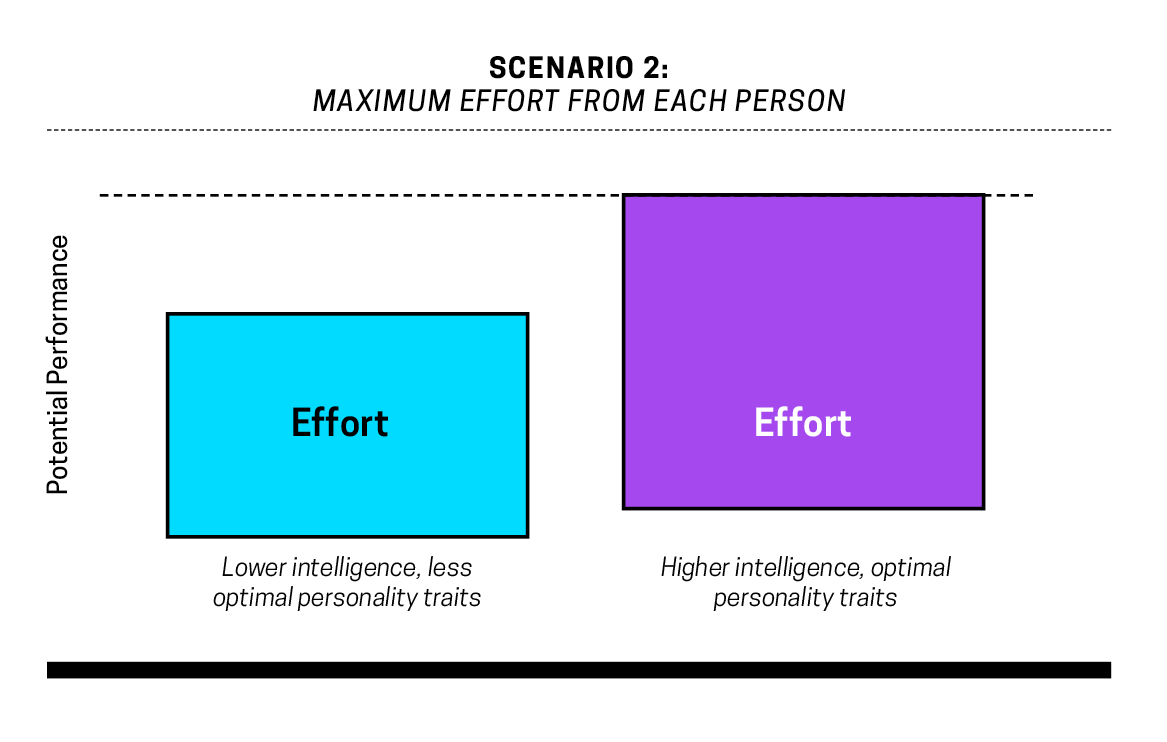

Given what we know about intelligence and personality, there’s no reason to expect growth mindset should work. We know intelligence and personality are, by far, the most powerful predictors of success at school and work. Therefore, even with the right mindset, someone with less than ideal intelligence or personality characteristics will always be at a disadvantage to someone blessed with more of each.

It would also be strange if someone could simply shift their mindset and—independent of their intelligence, personality traits, and other individual factors—increase their performance at school or work. That would be a remarkable performance shift from a relatively minor effort. The examples below bring this to life. It’s certainly possible for someone with fewer natural gifts to outperform someone with more natural gifts if they exert far more effort (Scenario 1).

But once the person with natural gifts puts effort into being a higher performer, they will outperform the less gifted person (Scenario 2).

… Because Personality and Intelligence Don’t Change That Way

Growth mindset advocates argue you should believe in your ability to change your personality and intelligence. The strong science in the areas of personality and intelligence challenges that possibility. Intelligence (fluid intelligence, or your “processing power”[28]) and your core personality are generally stable over time.[29]

It’s certainly possible for you to learn about more things (this is our “crystallized intelligence”[30]), but that doesn’t increase your brain’s core processing power. Knowing more things isn’t the same thing as being more intelligent.

Similarly, our core personality traits are relatively fixed and typically don’t change over short time periods (3 to 5 years) as growth mindset fans claim is possible. When those traits change over longer time periods (10 to 30 years), it’s normally due to a dramatic life event (e.g. death of spouse, severe illness) or the same predictable personality changes that happen to everyone as we age.[31] It’s important to note those personality changes happen to you. They’re rarely a result of you consciously deciding to, or making a sustained effort to, change them.

To be clear, the most extensive and conclusive science shows our intelligence and personality traits are stable and undergo very limited change in adults. Those changes have no relationship to adopting a growth mindset.

But There Has to Be Something There!

Many reasonable people will ask: “If growth mindset doesn’t do what it promises, how come when I changed my mindset, I was able to overcome obstacles, or succeed where I previously couldn’t?”

There are a multitude of reasons people succeed at something after they first fail or underperform. The most obvious reason is they were capable the entire time, but didn’t try (or didn’t try hard enough). When they either tried, tried again, or tried harder, their existing capabilities allowed them to succeed.

Why isn’t that the epitome of growth mindset? First, because Dweck explicitly states growth mindset isn’t about effort.[32] Second, because you could put a less intelligent person in that same situation, have them apply the same mindset and the same amount of effort, and they wouldn’t achieve the same results. A less intelligent, personality-disadvantaged individual with a growth mindset will not outperform a more intelligent person with a growth mindset. The difference in achievement will be due to fixed characteristics like intelligence and personality, not to someone’s mindset.

People can also succeed at Time B where they didn’t succeed at Time A if they apply any of the scientifically proven methods to improve their performance at work. Those methods include setting goals, changing their behaviors, working harder, influencing better, or any of the other scientifically proven approaches I wrote about in 8 Steps to High Performance.[33]

In that book, I also cautioned that our core personality traits and intelligence are the largest factors in our success, and that one’s efforts and mindset will only move someone as far as those fixed characteristics will allow.

It would be wonderful if everyone engaged in all of those scientifically proven tactics so they could be as successful as possible. There’s no proof that also having a growth or fixed mindset would make any difference in the outcome.

Why You Should Avoid the Term “Growth Mindset”

You may believe there’s no harm in urging people to have a growth mindset. It may not hurt if, when you say that term, you mean someone should engage in tactics proven to make them more successful. But, in that case, why not tell someone specifically they should try harder or practice more or keep a positive attitude?

If you mean they should have a “growth mindset” (they should believe intelligence and personality can change, and they’ll be more successful for that belief), you’re harming individuals who may not be able to succeed, and doing nothing for people who would have succeeded anyway.

The growth mindset concept captures the best of our humanistic spirit (anyone can improve if they just believe!) and confirms the worst of our scientific ignorance (can’t anyone improve if they just believe?).

It purports to solve a problem that may not exist, or that may be more effectively addressed by other means if it does exist. In any case, a growth mindset intervention would be sharply constrained by the more powerful influence of intelligence and personality.

The science is clear: Adopting a growth mindset does not meaningfully increase performance in adults or children. You become a higher performer when you engage in any of the multitude of activities that are proven to make you a high performer. If we want to help more people to succeed, let’s focus our efforts there first.

Marc Effron is the publisher of TalentQ, cofounder of the Talent Management Institute, and the president of The Talent Strategy Group, which helps the world’s largest and most successful corporations create incisive talent strategies and powerful talent-building processes. He’s also the author of 8 Steps to High Performance: Focus on What You Can Change (Ignore the Rest).

[1] . Schmidt, Frank L., and John Hunter. “General mental ability in the world of work: occupational attainment and job performance.” Journal of personality and social psychology 86, no. 1 (2004): 162.

[2] Oshio, Atsushi, Kanako Taku, Mari Hirano, and Gul Saeed. “Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta-analysis.” Personality and Individual Differences 127 (2018): 54-60.

[3] Bandura, Albert. “Self‐efficacy.” The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology (2010): 1-3.

[4] Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. “Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey.” American psychologist 57, no. 9 (2002): 705.

[5] Latham, Gary P. Work motivation: History, theory, research, and practice. Sage, 2012.

[6] https://bible.knowing-jesus.com/Proverbs/14/23

[7] http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhism/dp20.htm #276

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Power_of_Positive_Thinking

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Little_Engine_That_Could

[10] Dweck, Carol S. Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Digital, Inc., 2008.

[11] Dweck, Carol. “What having a “growth mindset” actually means.” Harvard Business Review 13 (2016): 213-226.

[12] https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/09/23/carol-dweck-revisits-the-growth-mindset.html?cmp=cpc-goog-ew-growth+mindset&ccid=growth+mindset&ccag=growth+mindset&cckw=%2Bgrowth%20%2Bmindset&cccv=content+ad&gclid=Cj0KEQiAnvfDBRCXrabLl6-6t-0BEiQAW4SRUM7nekFnoTxc675qBMSJycFgwERohguZWVmNDcSUg5gaAk3I8P8HAQ

[13] Dweck, Carol S. Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Digital, Inc., 2008.

[14] Dweck, Carol. “What having a “growth mindset” actually means.” Harvard Business Review 13 (2016): 213-226.

[15] Ibid

[16] Bahník, Štěpán, and Marek A. Vranka. “Growth mindset is not associated with scholastic aptitude in a large sample of university applicants.” Personality and Individual Differences 117 (2017): 139-143

[17] Rienzo, Cinzia, Heather Rolfe, and David Wilkinson. “Changing Mindsets: Evaluation Report and Executive Summary.” Education Endowment Foundation (2015).

[18] Li, Yue, and Timothy C. Bates. “You can’t change your basic ability, but you work at things, and that’s how we get hard things done: Testing the role of growth mindset on response to setbacks, educational attainment, and cognitive ability.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 148, no. 9 (2019): 1640.

[19] Burgoyne, Alexander P., David Z. Hambrick, and Brooke N. Macnamara. “How Firm Are the Foundations of Mind-Set Theory? The Claims Appear Stronger Than the Evidence.” Psychological Science (2020): 0956797619897588.

[20] Sisk, Victoria F., Alexander P. Burgoyne, Jingze Sun, Jennifer L. Butler, and Brooke N. Macnamara. “To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses.” Psychological science 29, no. 4 (2018): 549-571.

[21] Blackwell, Lisa S., Kali H. Trzesniewski, and Carol Sorich Dweck. “Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention.” Child development 78, no. 1 (2007): 246-263.

[22] https://www.buzzfeed.com/tomchivers/what-is-your-mindset?utm_term=.vuYA4ZbJe#.tuR-8Wa1OV

[23] Haimovitz, Kyla, and Carol S. Dweck. “Parents’ views of failure predict children’s fixed and growth intelligence mind-sets.” Psychological Science 27, no. 6 (2016): 859-869.

[24] Yeager, David S., Paul Hanselman, Gregory M. Walton, Jared S. Murray, Robert Crosnoe, Chandra Muller, Elizabeth Tipton et al. “A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement.” Nature 573, no. 7774 (2019): 364-369.

[25] Payne, Stephanie C., Satoris S. Youngcourt, and J. Matthew Beaubien. “A meta-analytic examination of the goal orientation nomological net.” Journal of Applied Psychology 92, no. 1 (2007): 128.

[26] Caniëls, Marjolein CJ, Judith H. Semeijn, and Irma HM Renders. “Mind the mindset! The interaction of proactive personality, transformational leadership and growth mindset for engagement at work.” Career Development International (2018).

[27] https://finance.yahoo.com/news/satya-nadella-says-book-gave-180034370.html

[28] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/fluid-intelligence

[29] Deary, Ian J. “The stability of intelligence from childhood to old age.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 23, no. 4 (2014): 239-245.

[30] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/fluid-and-crystallized-intelligence

[31] Terracciano, Antonio, Robert R. McCrae, and Paul T. Costa Jr. “Intra-individual change in personality stability and age.” Journal of research in personality 44, no. 1 (2010): 31-37.

[32] https://stanfordmag.org/contents/when-success-sours

[33] Effron, Marc. 8 Steps to High Performance: Focus on What You Can Change (Ignore the Rest). Harvard Business Press, 2018.