If the pandemic taught us anything, it’s that change is inevitable and unpredictable. It’s what you choose to do with it that could shape the rest of your career.

By Dave Ulrich

Where would taxi drivers be without Uber? Hoteliers without Airbnb? Retailers without Amazon? Well, probably in a much better place than they are right now.

Transformations occur all the time in industries where new firms disrupt patterns of competition. And if you refuse to acknowledge the ever-present tides of change, you’ll end up a lot like, say, Blockbuster. (Rest in peace, old friend.)

An executive once said that while it may take 30 or more years to build a firm, that company could be toast in 2 years if it can’t keep up with the times. In fact, of the original Fortune 500 firms, just 60 exist today.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

But there are smart organizations that know how to adapt and survive. General Electric became an ecoimagination and digital firm. IBM shifted to services. Apple moved into retail, phones, music, and watches. These companies didn’t much like their visions of getting left in the dust, so they seized new business opportunities and became even bigger success stories instead of cautionary tales.

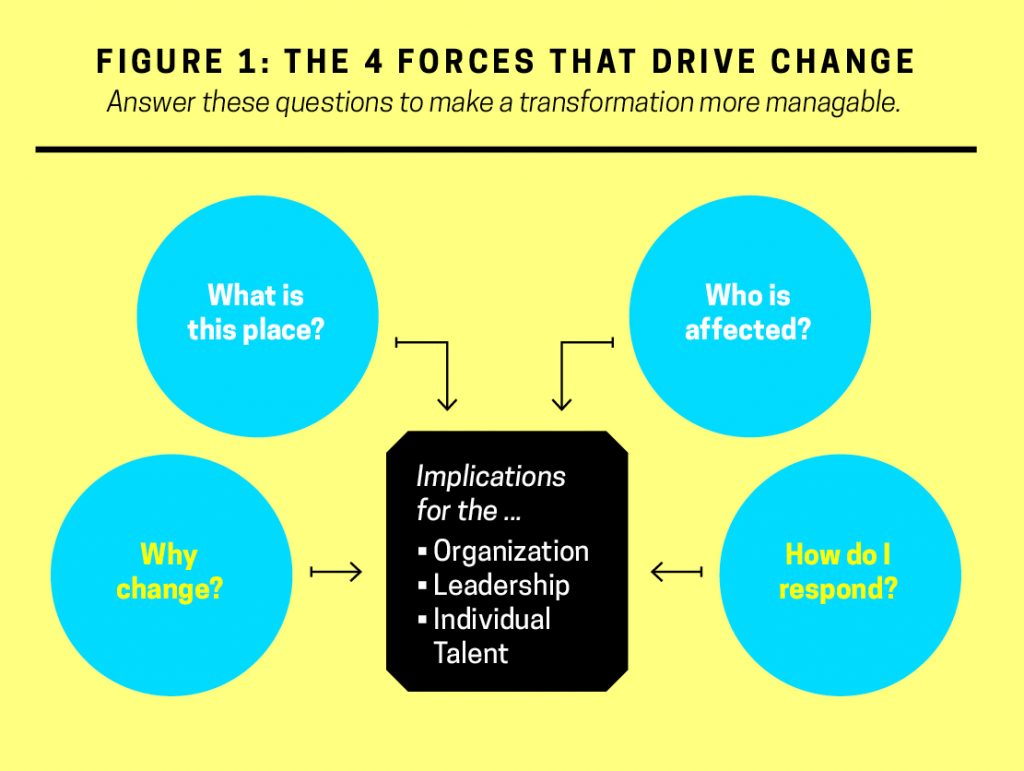

If change happens everywhere we turn, then how do leaders help organizations and people adapt to it? First, it’s important to understand the four forces creating change so that it can be an opportunity, not a threat; understood, not imposed; an avenue of growth, not despair; and anticipated, not managed. And then it helps to delineate the implications of these four forces for how to lead change for organizations, leadership, and individuals. Start here.

4 Forces That Drive Change

In business strategy, Michael Porter articulated five forces that shape how a firm differentiates to win. In change, there are four forces that capture the drivers behind change. When leaders can delineate, discuss, and demystify these four forces, change is less an overwhelming tsunami and more part of a predictable weather pattern (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The 4 Forces That Drive Change

Answer these questions to make a transformation more manageable.

Force #1: Why Change?

A business leader whose firm operated in more than 80 countries asked us how he could respond to the changes happening within countries he visited. Another colleague asked us how to organize our complex world into a relatively simple framework that might help her anticipate industry changes.

While there are many frameworks capturing the relevant trends in the business context, we prefer a typology of six categories (known as “STEPED”) that leaders can use to understand how contextual changes affect how businesses operate:

• Social (expectations, values, lifestyle, haves and have-nots)

• Technological (information access and frequency, digital economy including AI and IDT)

• Environmental (public policy, social responsibility, care for the planet)

• Political (regulatory shifts, political interests)

• Economic (industry evolution, industry consolidation)

• Demographic (age, education, and background of people)

Using this framework, leaders can better diagnose geographic or industry trends to help businesses anticipate the future and position themselves to win. When our colleague would visit a country where her company did business, he would ask for trends in these six areas to help him understand the context of his organization’s strategic choices.

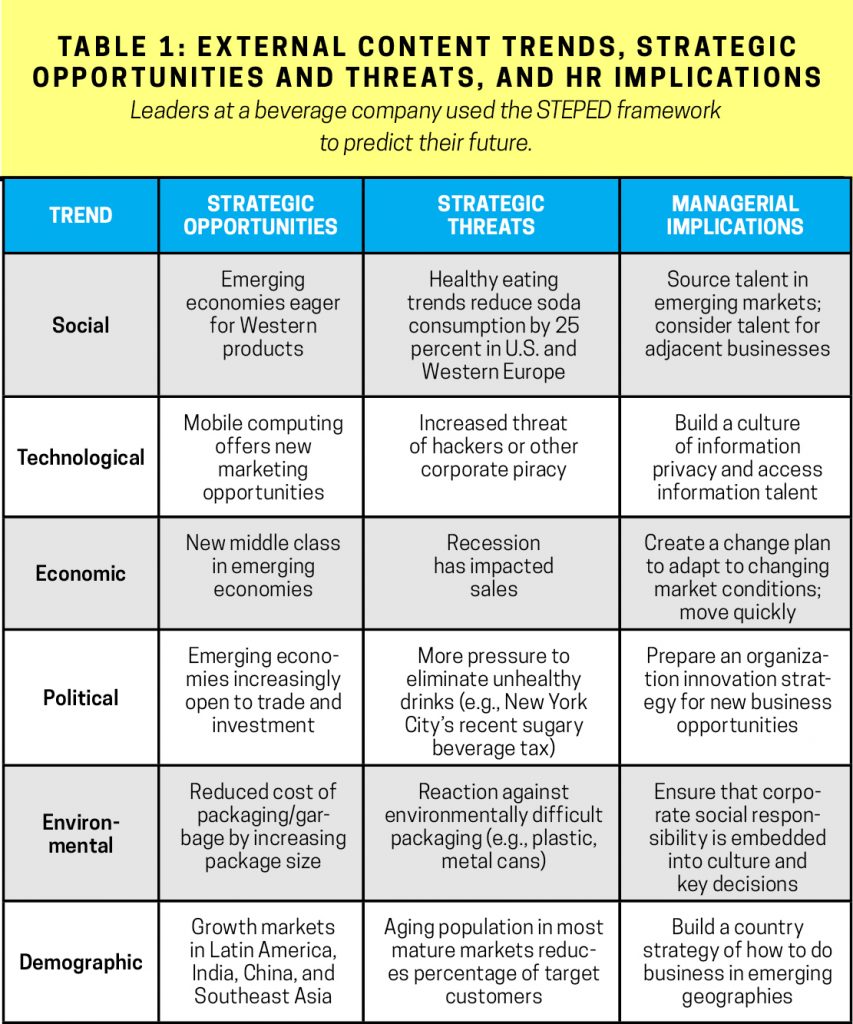

The STEPED framework can be used to review industry trends. For example, the top team in a beverage company discussed how the environment would shape their business in the future (see Table 1).

Table 1: External Content Trends, Strategic Opportunities and Threats, and HR Implications

Leaders at a beverage company used the STEPED framework to predict their future.

If leaders can articulate and identify trends in these six areas, they can anticipate the future and prepare a response. Suddenly, change becomes less abstract and threatening and more specific and controllable.

Force #2: What Is the Pace?

Over the years, VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity) has become an accepted tenant of management. Defined by the U.S. military, VUCA describes general conditions facing organizations. In response to these conditions, the military pivoted toward using small, elite Special Forces teams (Rangers, Delta Force, Seal teams) to move quickly to respond to and resolve conflicts.

Organizations have followed suit and created a hub-and-spoke strategy where spokes represent small ventures that operate autonomously from the headquarters’ hub to respond to VUCA opportunities.

As VUCA would predict, the world continues to change, dramatically at times, with the half-life of knowledge and the time allowed to adapt getting ever shorter. To keep up with constant social, technological, economic, political, environmental, and demographic changes, VUCA needs to evolve to the next phase, known as DRET.

Volatility to Discovery: Change requires discovery, which comes from reinventing, seeking a share of opportunity (not market share), and managing the expectations of continual change.

Uncertainty to Risk: With an inability to predict the future comes a requirement to understand and manage risk. Managing risk includes increasing predictability, reducing variability, and creating control mechanisms.

Complexity to Ecosystem: Complexity is about confusing multiple streams of activity. Anticipating it means shifting to an ecosystem logic where the focus is on partnership, differentiated teams, paradox navigation, and networks.

Ambiguity to Transparency: Reality isn’t played out in public forums where access to information becomes ever more present. Because of this, we must sense both structured and unstructured data to find trends.

Demystifying the pace of change into specific responses helps leaders anticipate and respond to change.

Force #3: Who Is Affected?

If STEPED defines opportunities and threats in the business environment, and DRET defines the intensity and pace of change, understanding stakeholder expectations defines who to satisfy to help the firm succeed.

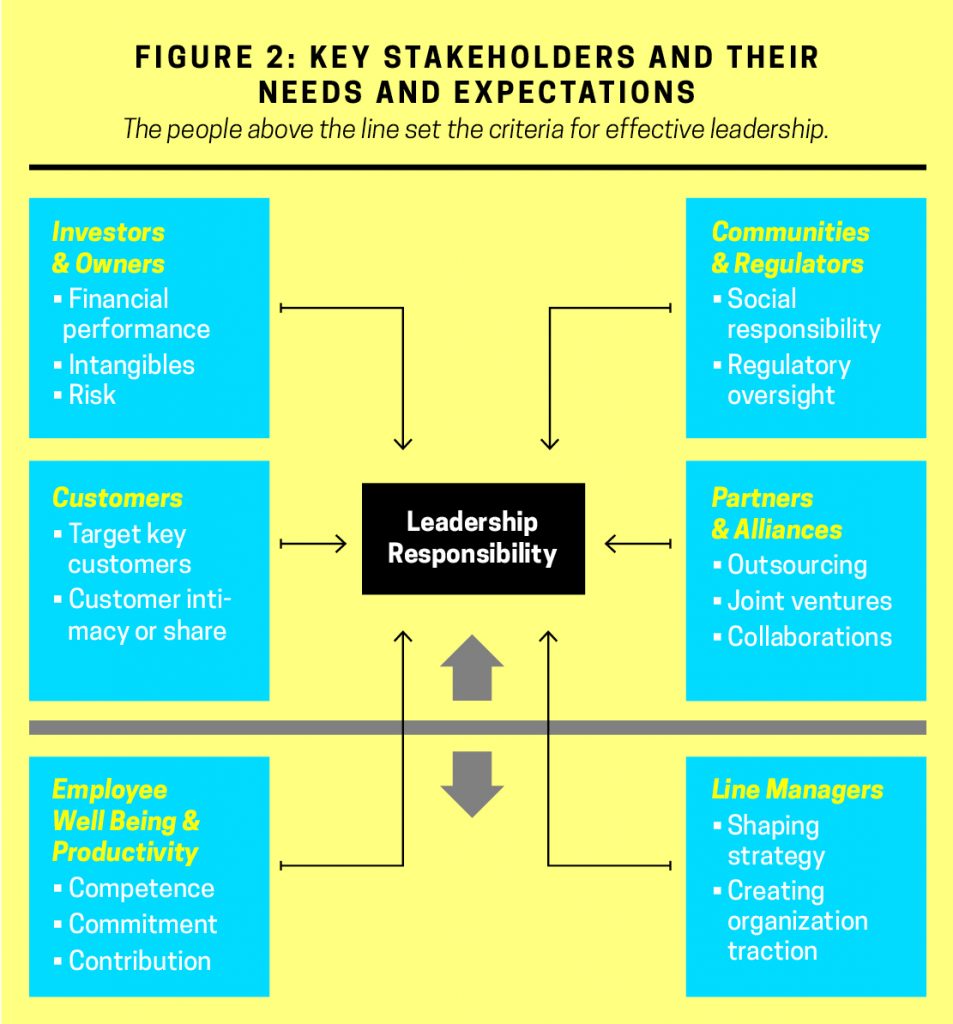

Because of contextual and intensity changes, stakeholder expectations are dramatically changing, too. Figure 2 captures many of the stakeholders for a company and what they likely expect from their interactions with that organization. These stakeholder expectations set the criteria for effective leadership.

Figure 2: Key Stakeholders and Their Needs and Expectations

The people above the line set the criteria for effective leadership.

Increasingly, the line between external customers, investors, communities and regulators, and partners (above the line in Figure 2) and employees and line managers (below the line) is being blurred. More leaders are being asked to help deliver customer share, investor intangibles, community reputation, partnership cooperation, employee wellbeing, and organization success.

Force #4: How Do I Respond?

All the changes in external context also affect how people respond when playing the game. Their responses to workplace change—and workplace behavior itself— are in turn influenced by these six societal shifts (Six “I’s”) that put enormous pressure on shaping the emotional impact of how we live and work.

- Intensity: We tend to think of our lives like we’re on a reality TV show, where intensity and insults replace insight and civility, emotional outbursts matter more than reasoned dialogue, and we’re motivated to “win” generally at the expense of others.

- Individuation: In a world of hyperfree agency, we win by taking control of our careers, maximizing our self interests, and eschewing long-term commitment to an organization. As one Silicon Valley executive said, “My people go to lunch and come back with a job offer.” We’re encouraged to be authentic by taking charge of our lives and becoming our own brand.

- Isolation: Research shows social isolation has a stronger impact on mortality than smoking, drinking, obesity, depression, or anxiety. Too bad we’re working more and more in SOHO (small office, home office) settings. As digital natives, we’re spending up to 7.5 hours a day in front of a screen. When we do have personal contact, it’s frequently through social media; we’re connected, but not connecting. No wonder loneliness persists.

- Indifference: Throughout the world, the next generation has learned to moderate expectations. Our primary parenting goal used to be to provide our kids with better opportunities to live than we ever had; now maturing adults get an education, but not a job, and even less often a career. As voters, we’re increasingly cynical about politicians having our best interests in mind.

- Immediacy: Our sense of time and duration has also shifted. Many of us seek immediate gratification without investing in long-term preparation. “Long term” feels like next week. We have disposable relationships, and we’re far less likely to get married.

- In-Group (Labels): We see a world with increasing subgroups. The gap between the rich and the poor, and the haves and the have-nots, has increased. Using statistics, we can quickly find patterns that label people into subgroups. Managing information from cookies reinforces these labels and becomes the focus for tailored advertising, customized products, and unique offerings.

In 1976, 27 percent of Americans lived in landslide counties where political elections were decided by more than 20 percent. In 2016, this grew to over 60 percent. This means most people choose to live in neighborhoods with like-minded and socially similar individuals. We don’t spend time with people who aren’t like us.

These six societal affective trends are discouraging, to say the least. Yet they define how individuals live, and so have the potential to undermine and destabilize organizations. Employees who are demoralized by these factors create organizations without capacity to respond to STEPED or DRET conditions and without ability to serve key stakeholders. It isn’t a surprise that employee engagement scores on most surveys are at an all-time low. Leaders who relish change must shift these seemingly negative trends into positive opportunities to help their organizations become communities of action where:

• Employees channel intensity to create value for others.

• Individual self-interest is replaced by shared purpose.

• Isolation is overcome with personal connection.

• Indifference shifts to renewal.

• Immediacy for today’s results becomes the pathway for a long-term vision or strategy.

• Labels are replaced with valuing differences that make teams stronger than individuals.

When these six contextual trends turn positive, we replace cynicism with commitment and isolation with community. To see opportunities in change, leaders must be aware of these trends and influences and be prepared to deal with their effects.

Defining and understanding these four forces for change helps leaders anticipate and respond to the inevitability of change. Yes, of course change happens. But it isn’t in an overwhelming complexity. Rather, it’s a defined set of predictable patterns that we can demystify—and act on.

Where We Go From Here

By recognizing the four forces for change, leaders can anticipate and adapt to changes that occur for organizations (how do we create a more responsive or agile organization?), leadership (how do we identify and develop the leadership capability of our organization?) and individuals (how do leaders help individuals become change-agile?). When we recognize and execute the nine actions listed below, we’re more able to respond to change.

How Do We Create a More Responsive, Agile Organization?

1. Redefine the definition and logic of “organization.” Traditional views of organization, grounded in work by German sociologist Max Weber, drew insights from bureaucracies like the Catholic Church and German military. In these legacy views, organizations succeeded and survived by creating morphology or structure with a clear line of authority, chain of command, decision rights, spans of control, specialization, and division of labor where each employee knew his role and responsibilities.

As the four forces have evolved, organization logic has also evolved to emphasize systems and organizational alignment (such as STAR, McKinsey 7S, or Health) where the goal is to align organization systems. With more external change, organization logic evolved to define organization as a set of capabilities or design criteria that meet external requirements.

With even more of the four forces, the greater challenge for organizations is to adapt quickly, because what was right yesterday isn’t right today and won’t be right tomorrow. This leads to emerging organizational forms like ambidextrous, lattice, holistic, holacracy, boundaryless, and market-based networks.

In our work on market-oriented eco-organizations (MOE), an organization’s success comes from its ability to adjust to change, which is often referred to as agility, flexibility, learning, transformation, revitalization, and so forth.

Organization change with structure assumptions focuses on de-layering or right-sizing the organization; with system assumptions, the change focuses on alignment of resources; with capability assumptions, the change focuses on building the right culture or identity; and with eco-organization logic, the change focuses on creating capability-based networks or ecosystems.

Amazon is a great example of an emerging organization that builds capabilities across its network of companies. Another setting for the emerging organization logic comes from the rise of private equity firms, where their current focus is on sharing capabilities across the portfolio companies through change leadership.

2. Create the right capabilities for success. With the four forces for change, leaders focus their organizations on deploying the right capabilities more than structure. Capabilities represent what the organization is known for and good at doing. At times, these capabilities are inside the organization, and with the MOE, they’re embedded in the organization network.

In our work, we’ve found that there are three critical capabilities to win in rapidly changing markets characterized by the four forces:

• Customer-oriented, where the firm can anticipate, shape, and respond to current and future customers.

• Innovation, where the firm seeks discovery in all elements of the business model.

• Agility, where the organization moves quickly and transparently into (and out of) new opportunity spaces.

Google’s organization is focused around sourcing information on all three capabilities. Google acquires, analyzes, and applies information on customers through big data searches tracking customer searches; promotes innovation across the businesses under the Alphabet holding company umbrella; and encourages rapid decision making to discover, enter, penetrate, and (if required) exit new markets.

3. Embed change-able disciplines throughout the organization. To respond to the four forces of change, leaders implement a host of initiatives including strategic clarity, technological innovation, operational excellence, and customer service. Research has shown that 25 to 33 percent of these initiatives are fulfilled on time and completed within budget.

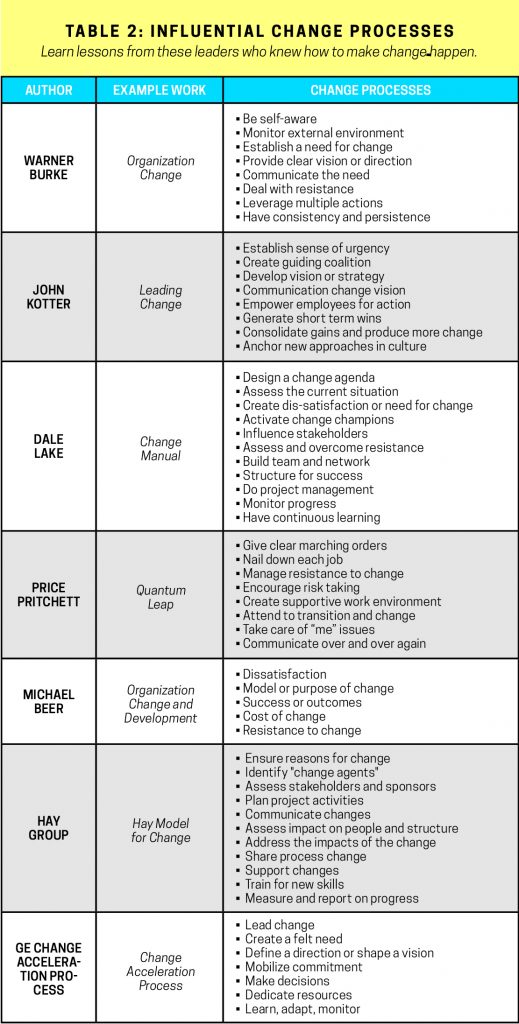

Leaders have created an organization discipline for making change happen, which often captures the key steps for implementing change and then instills discipline in deploying each of these change-able disciplines. Some of the influential change processes are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Influential Change Processes

Learn lessons from these leaders who knew how to make change happen.

As leaders adapt these insights into a disciplined process for change in their organization, they can improve the ability to implement any number of corporate initiatives. At General Electric, they developed a “change acceleration process” (CAP) that they apply to a number of change initiatives to increase the ability to make change happen. Their logic is to turn what they know about change (their processes) into what they do (their actions). This checklist logic offers discipline on change that any leader can apply to any business initiative.

How Do We Identify and Develop the Leadership Capability of Our Organization?

4. Create leadership capability more than individual leaders. Individual leaders matter in change, but collective organization leadership matters even more for sustained change. An individual leader’s influence exists as long as the head honcho remains present. With collective leadership, however, impact is widely distributed throughout the organization and across time when any individual figurehead moves on. Leaders create leadership by sharing decision-making, developing managers through experiences and training, and by coaching future bosses to improve.

5. Establish a leadership brand. With the stakeholder forces for change, the right leadership does not show up in an idealized set of competencies, but the competencies that reflect what customers and investors expect now and in the future. As customer and investor expectations change ever more dramatically, leaders must adapt competencies to respond. When leadership competencies reflect customer and investor promises, the leadership brand becomes a sustainable source of change. For example, we have created a leadership capital index that can be tracked to give investors confidence in future leadership capability.

6. Learn to navigate paradox. Many organizations seek a single underlying factor that will ensure leadership effectiveness. In recent years, leaders have been encouraged to have emotional intelligence, then learning agility (or grit, resilience, growth mindset, or perseverance). In our research, navigating paradox has become the next wave in the evolution of leadership effectiveness. Paradoxes exist when seemingly contradictory activities operate together. We experience paradoxes in daily life as captured by many popular phrases: tough love, do more with less, oil and vinegar, sweet and sour, work-life balance, catch 22, go slow to go fast, good and evil, and so forth. When these inherent contradictions work together, success follows. Instead of focusing on “either-or” paradoxes, you should emphasize “and-also” thinking.

In management thinking, paradox concepts have shown up in many terms: behavioral complexity, polarity, flexible leadership, duality, dialectic, competing values, dichotomies, competing demands, and ambidexterity. We’ve applied these concepts to accounting, marketing, technology, strategy, and human resource literatures and practices. There’s an increasing body of evidence that navigating paradox has positive implications within organizations. With the four forces for change, organizations have to adapt to win; organizational agility increases when leaders encourage disagreement that comes from navigating paradox.

How Do Leaders Help Become Changeable?

7. Encourage a growth mindset so that learning occurs. According to research, about 50 percent of how we think and act is nature, tied to our lineage and DNA. The other 50 percent is nurture, which we can learn and grow. Staffing and matching an individual’s predispositions to a particular work assignment builds on the nature logic. Helping individuals learn and grow encourages nurturing.

Leaders can help employees acquire and enhance their growth mindset, which means that people are curious and willing to learn. We’re encouraged to explore alternatives, experiment with new ideas, seek best practices, and surround ourselves with people who aren’t like us. We increase our growth mindset when we have a sense of positive attachment to our peers and organization.

Leaders who create a spirit of teamwork allow employees to experiment, seek other options, and reinvent themselves—all of which are essential to personal change. Our growth mindset also increases when we see our failures or mistakes as opportunities to learn rather than be punished.

8. Help individuals manage risk. We’ve calculated personal risk taking as the will to win divided by the fear of failure. The will to win comes when we have ambition, agility, ability, and a growth attitude. These personal traits may be screened when hiring or promoting an individual. The fear of failure may be reduced by creating incentives that focus on process as much as results, by celebrating effort as much as outcome, and by turning failures into learning opportunities. When leaders increase the will to win and reduce the fear of failure, they help individuals respond positively to change.

One organization with an annual management meeting of the top 100 leaders by title invited 10 future leaders who were invited because of something they accomplished in the previous year.

What was especially telling was that five of the 10 had worked on an innovative idea and succeeded, and five had failed. The CEO lauded both groups, so that those who had the will to win could reduce their fear of failure.

9. Establish the neurology of opportunity. David Rock, a neurology researcher and consultant, has found that our brains are triggered by threat or opportunity. When we feel threatened, we shut down and shut off change. But when we sense opportunity, we’re much more open to change. Rock found that there are five primary factors that can be managed to trigger opportunity more than threat:

• Status: Try to reduce status between people.

• Certainty: Give people clarity about what will happen.

• Autonomy: Make sure people feel responsibility for their choices.

• Relationships: Help people learn to make and give bids and build social connections.

• Fairness: Ensure that people feel fairly treated.

Leaders who recognize and manage these neurological conditions will help employees find more opportunity than threat, and thus be able to change.

Change happens, but it need not be happenstance. By knowing the four forces for change and mastering the organization, leadership, and individual actions for responding to it, you can turn real threats of change into potentially huge opportunities.

So let me ask you this: Are you excited to enter the great unknown?

Dave Ulrich is the Rensis Likert Professor at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan and a partner at The RBL Group, a consulting firm focused on helping organizations and leaders deliver value. He studies how organizations build capabilities of leadership, speed, learning, accountability, and talent through leveraging human resources.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.