The authors evaluated 25,000 managers and reached a definitive conclusion: Women are more effective leaders than men.

By Joe Folkman, Ph.D., Joyce Palevitz, and Jack Zenger, Ph.D.

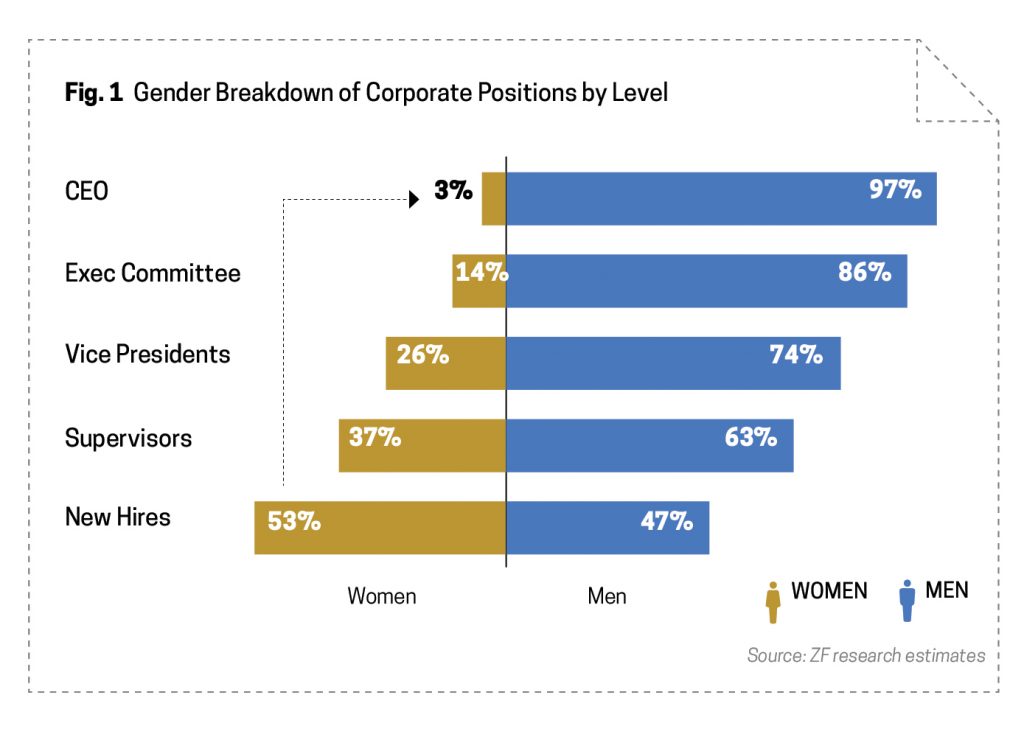

Much has been written about the glass ceiling that appears to limit how high women can go in large organizations. More women enter the corporate pipeline as new hires (53 percent to 47 percent), but by the time they become supervisors, the percentages shift to 37 and 63 percent. At the CEO level, only 3 percent are women (see Figure 1).

One might think, given the staggering difference between the numbers, that men are significantly more qualified for top jobs than women. We wanted to test that assumption using data we have gathered over the past six years. To assess each group’s effectiveness, we went directly to the people who know them best: managers, peers, direct reports, and others with whom they work closely.

Overall, we analyzed data from 336,923 raters who evaluated 24,634 leaders. Of these, roughly 65 percent were male and 35 percent female. Geographically, 64 percent were based in the United States, and 12 percent were executives, 23 percent in senior management, 30 percent in middle management, and 26 percent supervisors or individual contributors.

We also assessed 1,900 behaviors, which helped us identify the 49 that most effectively differentiate the best and worst leaders. In fact, high scores on these behaviors have been shown to predict such outcomes as turnover, customer satisfaction, profitability, sales, engagement, and discretionary effort of direct reports.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Our goal was simply to determine if male leaders are perceived by their colleagues as being more effective than females, or vice versa. We measured overall leadership effectiveness by creating an index composed of those 49 behaviors and then examining the data from all rater groups. On average, each leader was rated by 13 respondents.

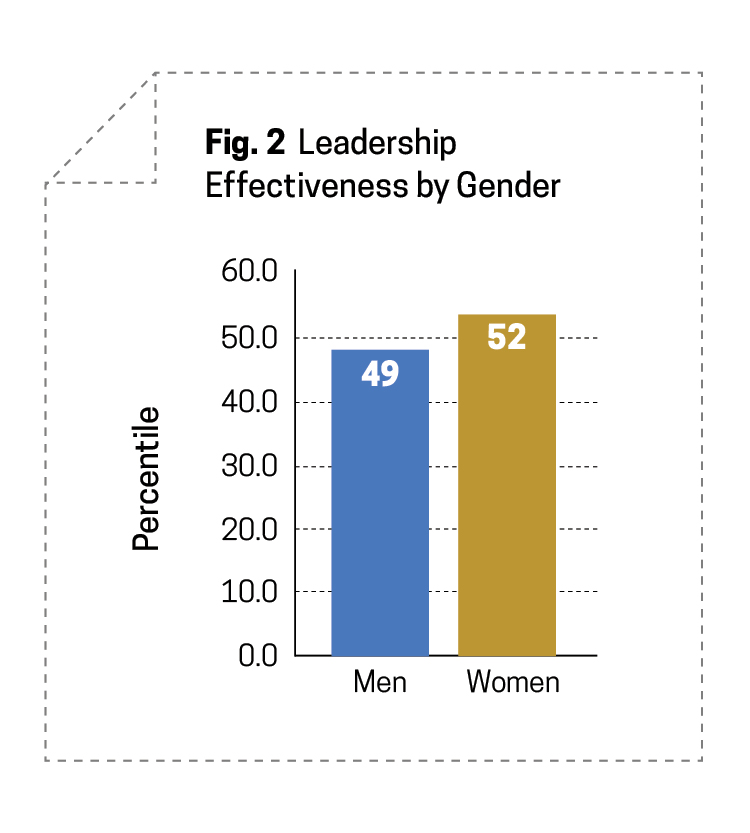

As you can see in Figure 2, women were rated more highly in leadership effectiveness than men. This may seem like a small absolute difference, but it’s statistically significant because of the large sample size.

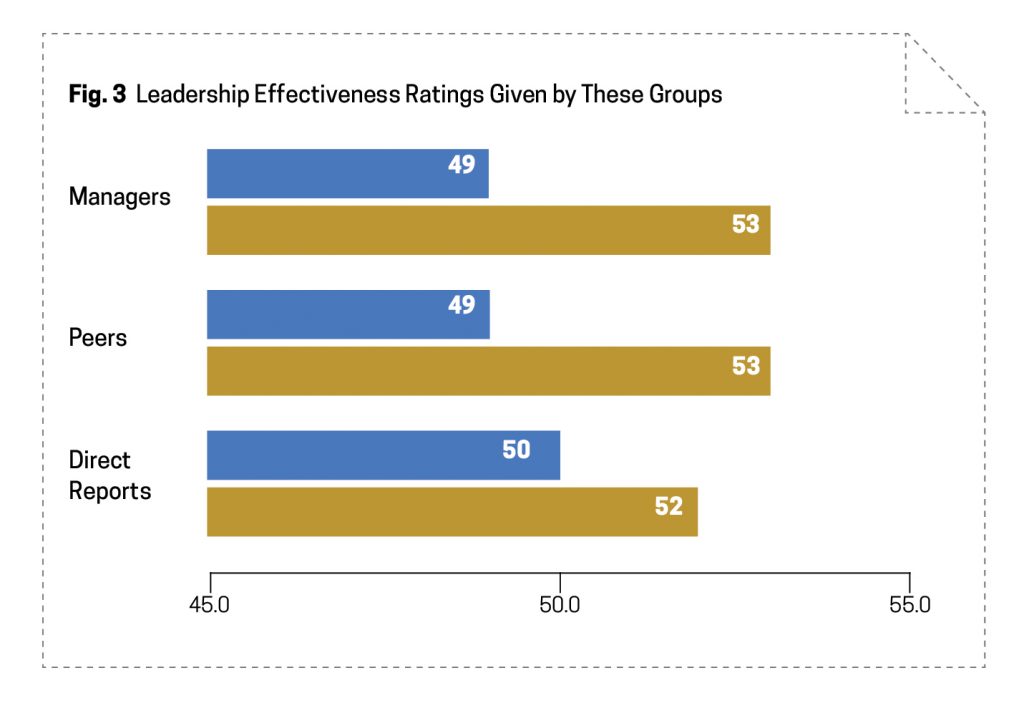

After we found this overall difference, we wondered whether some rater groups

favored women over men. Perhaps direct reports enjoyed working for female leaders more than males. In fact, we found that managers and peers (often the most critical raters) evaluated women more positively than men. While the results for all three rater groups are statistically significant, the difference in the way the genders are perceived is much wider for managers and peers than for their direct reports (Figure 3).

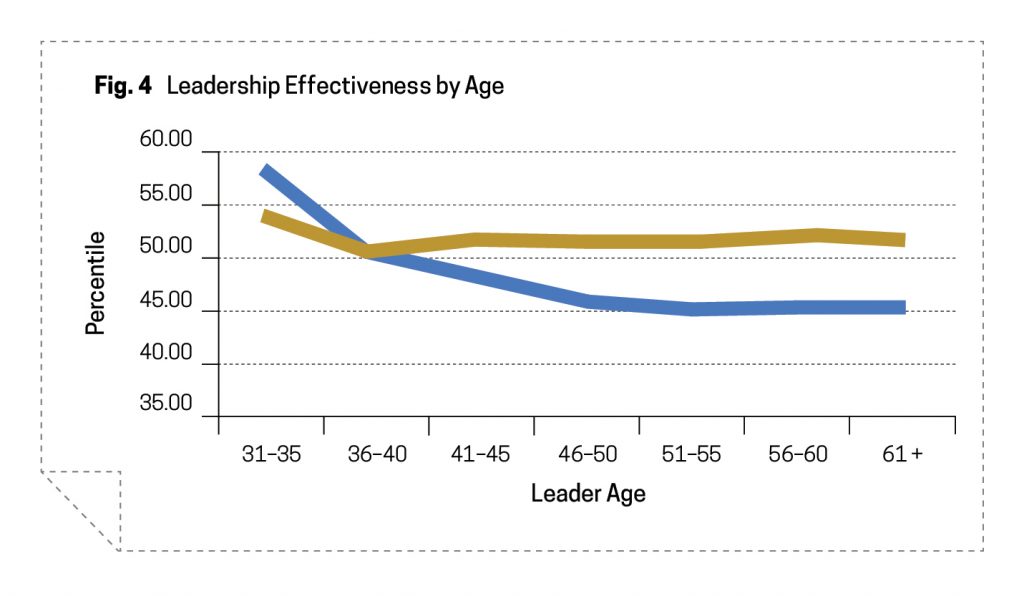

The next question to emerge was whether these perceptions held steady as women and men progress through their careers. That data was very insightful. Between ages 31 to 35, male leaders are rated more effective than female counterparts (Figure 4).

The group we studied consisted primarily of high-potential leaders who were selected for leadership development activities early in their careers. But the differences in effectiveness disappear at 36 to 40, and from then on we see a steady decline in the effectiveness of men and a slight improvement in women.

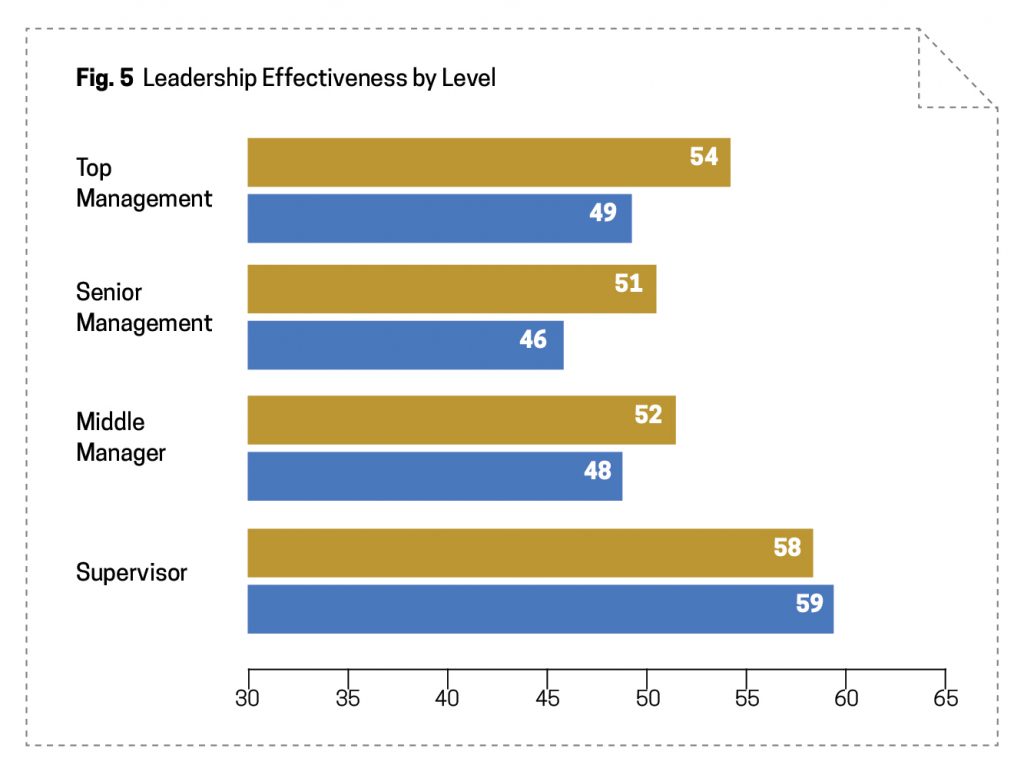

As leaders are promoted, expectations increase. We have higher standards for senior executives than for managers. Considering that the percentage of males increases as you ascend the corporate ladder, we wondered if leadership effectiveness would increase for men too. The answer was a resounding no (Figure 5).

The difference in perceptions of effectiveness between men and women in the executive and senior manager ranks is 5 percentile points in favor of women. The difference is 4 percentile points for middle managers, and for supervisors, men are rated slightly more positively than women. What this data clearly reveals is that women at senior levels are perceived to be more effective than their male counterparts.

Which Competencies Best Separate Men and Women?

Over a decade ago, we performed this same analysis on data from a single organization with an equal number of males and females. Our results were practically identical. Women were significantly more effective, although at that time there were no female executives. The executive leadership at the company found the results interesting, but suspected it might be some sort of anomaly unique to their company or our testing process.

Since then we have replicated this study over and over with the same results. When discussing the findings with others, we often hear this rationale: “Well, women are probably more nurturing than men and that explains the difference. That’s why they are held in such high regard.”

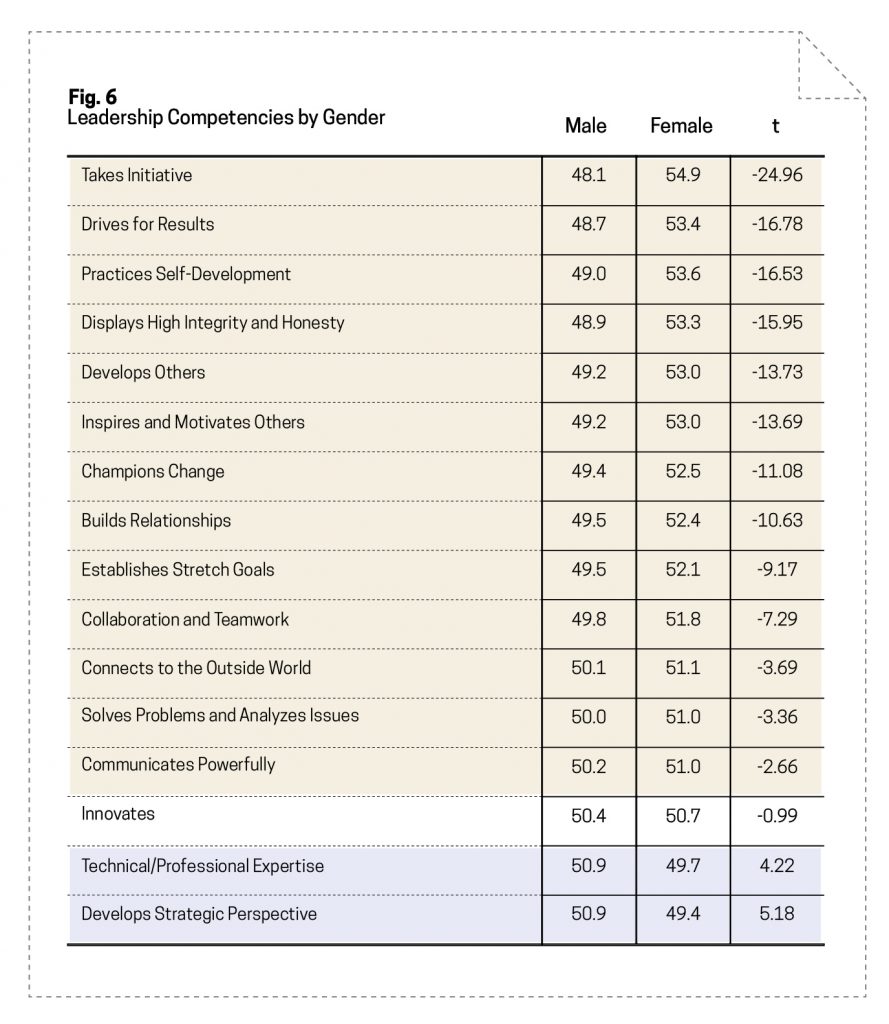

That is not what the data indicates. In our assessment of 49 items, we measured 16 competencies. We compared the results for both men and women on those competencies to understand where the largest differences exist. The table in Figure 6 shows the competencies sorted by t-value, or the departure from the expected finding.

In fact, women were rated significantly more positively on 13 of the 16 competencies. In addition, though women performed well in so-called nurturing competencies (such as “develops others” and “builds relationships”), the biggest deviation from the mean were in “takes initiative” and “drives for results”—both execution-oriented functions that are thought to be dominated by men. Evidently, women are more effective at getting critical projects started and achieving superior results too.

As you can see in Figure 6, men were rated more positively in two competencies: “technical/professional expertise” and “develops strategic perspective.” While these differences are not large, they are in fact statistically signifcant. These may be areas where women need improvement. Clearly having a “strategic perspective” is a critical gate that people must pass to be promoted to an executive position, and this may be part of the explanation for the lack of women in the most senior positions.

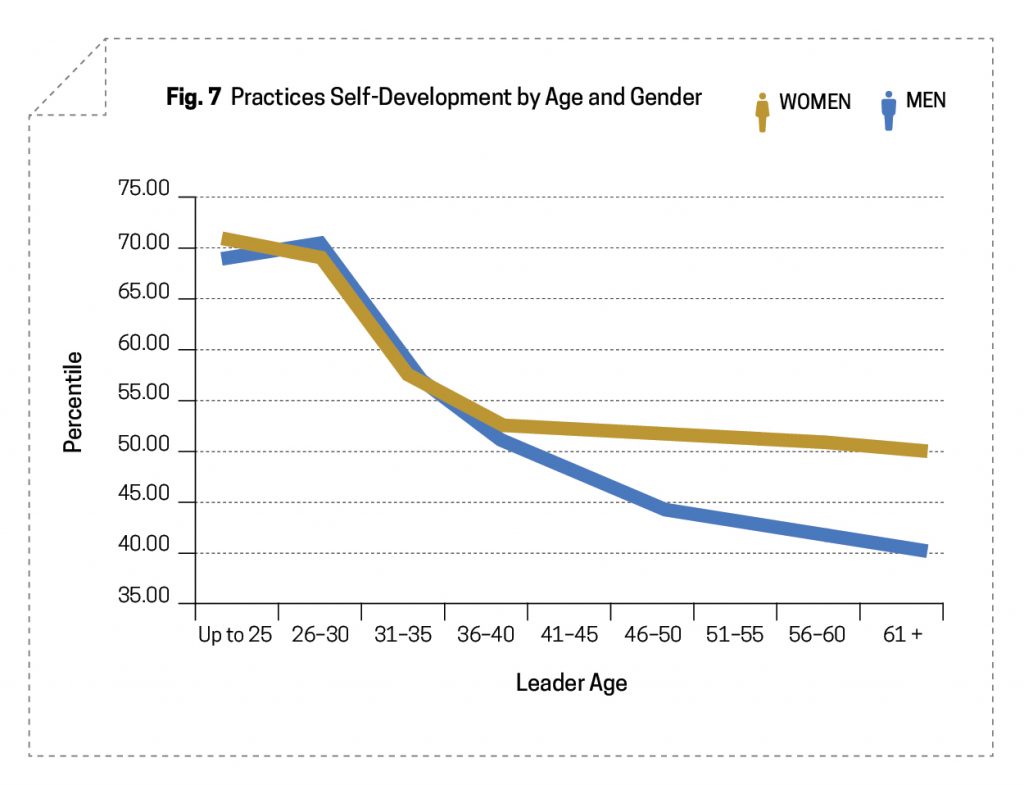

What’s more, we found one competency that sheds a great deal of light on why women tend to improve as they age, while men decline. The third-largest gender difference is “practices self-development.” This competency measures a leader’s willingness to ask others for feedback and be open to change based on that feedback.

We know that young leaders are more willing to ask for feedback, and that their willingness to act on what they hear leads to higher ratings for effectiveness. In Figure 7, you can see this. You can also see that effectiveness declines for both genders between the ages of 25 and 35, but that the steep decline slows for women around age 40.

We are not exactly sure why this occurs. However, women often tell us, “I’ve got to work harder and perform better to get the same rewards as a man in this company.” Perhaps this attitude keeps them open to continued growth and development. In stark contrast, an attitude we sometimes hear from men is a sense of entitlement that they are the chosen successor and will eventually be promoted to a position worthy of their talent and intelligence.

One last point: In our analysis, across all levels and age groups, men who asked for feedback were rated equally effective as their female counterparts. This is telling. It suggests that the effectiveness of any leader is not based on gender alone, but is driven by their commitment to continuous development.

What’s It All Mean? 5 Observations

Observation #1: Our measures of leadership effectiveness predict success in a variety of outcomes, from profitability to employee engagement. Women might be the secret weapon that organizations have been looking for to help them to succeed.

Observation #2: Women are more likely than men to rate themselves lower than where managers, peers, and direct reports score them. We believe that when women have access to this data, they may be more likely to confidently step into senior leadership roles.

Observation #3: Managers should use this research to challenge their assumptions about who’s ready for promotion. Armed with this level of gender intelligence, they should be at least equally likely to sponsor a woman as they are a man.

Observation #4: There are undoubtedly several reasons for fewer women being at the top of organizations. One may be fear, on behalf of senior executives and boards of directors, that promoting a woman is a risk. The data says otherwise. In Japan, approximately one-half of companies have no women in any managerial position. That’s where the United States and Europe were in the mid-1900s. We have clearly come a long way, but the finish line isn’t in sight just yet.

Observation #5: Finally, women might consider ways to make their strengths more visible, especially when it comes to technical expertise and strategy. An effective way to do this is through powerful behavior combinations that we call “competency companions.” Here’s an example: A woman who communicates powerfully and is a naturally gifted speaker can leverage this talent to win over others with her strategic insights, or another area she wants to build.

Joe Folkman, Ph.D. is the cofounder and president of Zenger Folkman, a professional services firm providing consulting and leadership development programs for organizational effectiveness initiatives. He is a highly acclaimed keynote speaker at conferences and seminars the world over. His expertise focuses on a variety of subjects related to leadership, feedback, and individual and organizational change.

Joyce Palevitz is a management consultant whose areas of expertise include leadership development and executive coaching, executive communication skills, team building and offsites, and business-to-business relationship management. She was previously the vice president of delivery services at Zenger Folkman.

Jack Zenger, Ph.D. is the cofounder and CEO of Zenger Folkman. He is the coauthor of seven books on leadership, including Speed—How Leaders Accelerate Successful Execution.