Good leaders can become great bosses, too—if they make these three pivots.

By Dave Ulrich

We know a lot about leaders and leadership: why they matter (to increase stakeholder value), who they are (personal characteristics that foreshadow success or failure), what they know and do (leadership actions and competencies), and how to be a better leader (build sustainability).

But do good leaders necessarily make good bosses? Leadership is about the theory and actions; being a good boss is about applying those actions. Leaders get things done; bosses motivate others to get things done. A good leader knows what to do; a good boss helps employees do the right things. Leadership is about a menu and ingredients; being a good boss is about creating a specific recipe that turns ingredients into a meal.

In the television series Chopped, contestants are given a basket of items and then expected to create a multicourse meal. A good chef turns those items into a gourmet meal. Likewise, leadership is about recognizing the suite of competencies; being a good boss is turning those generic competencies into specific actions that engage others.

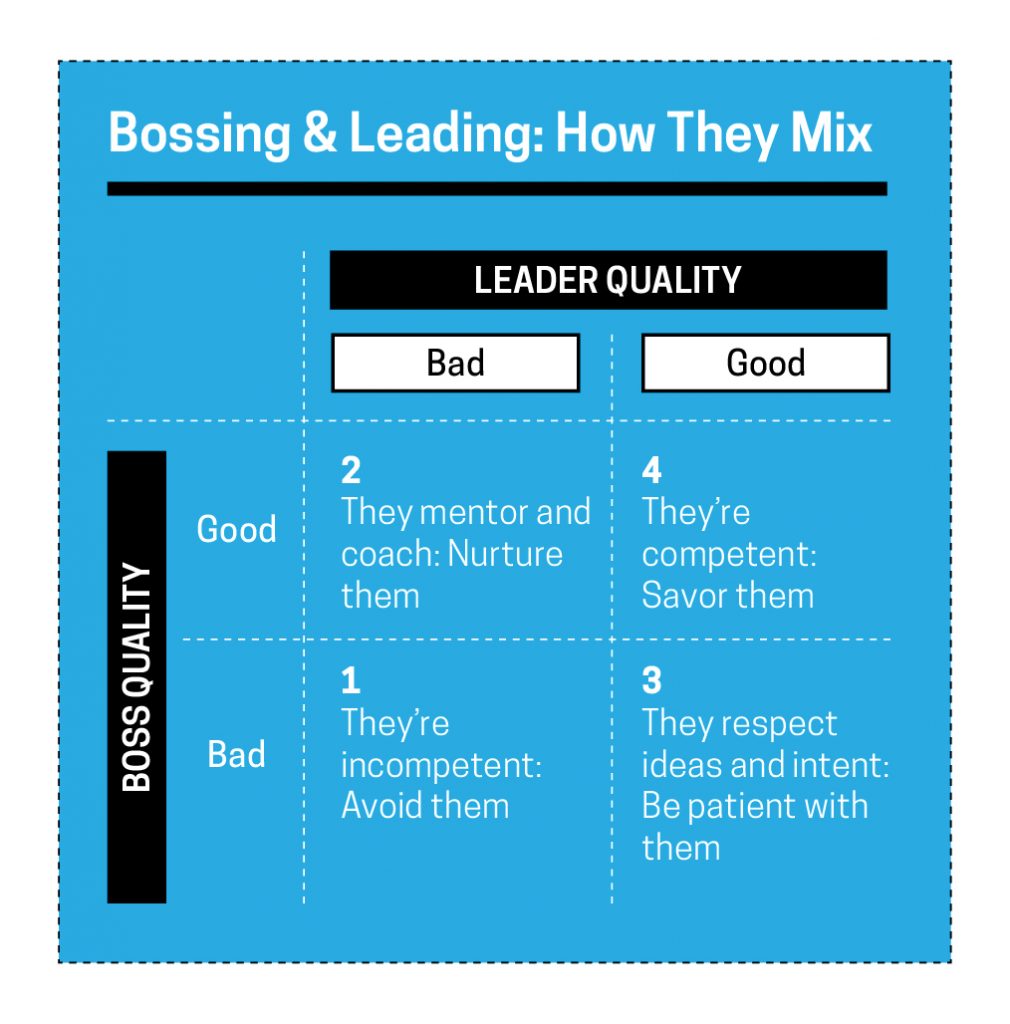

Consider the chart below: In cell 1, bad leaders are often bad bosses—avoid at all costs. In cell 4, good leaders are often good bosses; cherish and savor them every day and night. Cells 2 and 3 is where the differentiation occurs between bosses and leaders. Leaders have a set of competencies; bosses translate those competencies to guide employees.

In cell 2, a boss may be a good mentor or coach who creates an affirming and positive relationship, but not demonstrate many of the traditional leadership competencies. These bosses can become good leaders if they’re trained to recognize and sustain the underlying leadership skills they intuitively demonstrate.

In cell 3, the leader knows what to do, but often fails as a boss to do them. These are good leaders who can become great bosses.

When we ask people to think of bosses who most influenced their personal lives and professional success, we see quiet smiles reflecting fond memories. So, what makes these memorable bosses so impactful?

From years of research, writing about principles of leadership, and coaching hundreds of good leaders to become better bosses, I’ve discovered that there are three pivots that turn good leaders into great bosses.

Pivots are not shifts. Shifts are from-to. Pivots are and-also. So in the three pivots that follow, good leaders can become great bosses by nurturing and evolving their leadership qualities, insights, and competencies. Here’s how.

Pivot #1: Turn Leadership Authenticity into Leadership Value

Many suggest leaders be authentic, which is obviously a good thing. Authenticity is about the leader’s character and personal strengths. Value is more about how leaders build character in others and use their strengths to strengthen others. Bosses need to create authenticity in others more than themselves.

Authenticity becomes narcissism when it’s only self-interested. When bosses work to create value for others, their goal is less that they succeed, and more that others succeed. Less like helicopter parents, and more like parents who teach their children correct principles and let them govern themselves.

Becoming a value-based boss means that when business decisions are made, the boss thinks not just about personal choices but about how those choices will be received by others. In a crisis, instead of declaring “Here’s what to do,” a great boss asks himself how his choices impact those he leads. Leaders become better bosses when they move from intelligence (ideas) to emotion (sensitivity) to social connection (value).

When I coach leaders to be effective bosses, I often start by asking the aspiring boss two questions: First, what’s your preferred style (competencies, strengths, passions); second, what are you hoping to accomplish? I can then work through a stakeholder analysis to determine how the leader’s purpose will benefit those in his stakeholder network. Also, what he might require from those stakeholders to accomplish his goals.

Bosses who focus on others are known for caring as much as performing. This caring enables them to mentor, coach, and relish the success of others. They are multipliers who succeed by making others better.

Pivot #2: Convert Leadership Actions into Leadership Learning

In leadership workshops, I often ask, “How many are happy that intelligence (IQ) is not the biggest predictor of leadership success?” I suggest that if someone does not understand the question, they should raise their hand. Then I ask: “If it’s not intelligence quotient, what makes effective leaders?”

The answers I usually get are emotional intelligence (knowing oneself) or doing the right things. I suggest that EQ and action are good things, but not the most important for turning leaders into bosses.

Leaders who become great bosses not only have IQ, EQ, and action, but they also are committed to learning. There are many terms to describe an increased willingness and ability to learn: resilience, learning agility, growth mindset, grit, perseverance, hardiness.

Learning bosses continually experiment, reflect, and improve themselves. They enjoy new challenges, run toward failure because it’s a chance to grow, and see opportunity more than constraints. They take risks knowing that their desire to learn will help them get better. Employees very much appreciate working for these bosses, because their mistakes aren’t seen as fatal flaws that merit blame.

Leaders who are good bosses operate not virtuous cycles, but spirals. A cycle helps leaders become better at what they have done. A spiral implies that each cycle improves on the previous. When bosses succeed, they don’t assume that their success formula will be exactly the same in the future. When bosses fail, they learn from the failure and move on. In both cases, the learning leads to a virtuous spiral of continued improvement.

When I coach leaders to become better bosses, I like to say, “Tell me about a time when you made a decision that did not work. What did you learn? How did you apply that learning to your future decisions?” I also like to encourage leaders to acquire a growth mindset by asking them to face one of their largest personal or professional failures, and then to share what and how they learned from the experience. Leaders and bosses act; great bosses learn.

Bosses who learn inspire employees to do the same. These bosses encourage employee experimentation and often respond to employee concerns with “what do you think?” When employees make mistakes, these bosses don’t punish but learn and encourage employees to do the same. These bosses take informed risks, knowing that experiments won’t all work, but they will fail forward to make sure that the process for improvement matters even more than the outcome.

Pivot #3: Evolve from Leadership Clarity to Navigating Paradox

Most look to leaders for clear answers. In our (and other) research, we find that those who navigate paradox have the most business impact. Paradox means shifting from either-or thinking to and-also and focuses on questions more than answers. Navigating means being able to constantly adjust and adapt rather than managing and controlling—or even trying to stop.

In a business world of increasing volatility and complexity, right answers are more difficult than thoughtful questions. Locking into a definitive path may be a false positive when conditions inevitably change. By navigating paradox, leaders become bosses who are open to new ideas, encourage tension without contention, disagree without being disagreeable, and are not bound by the past.

In management thinking, concepts of paradox have shown up in many terms: behavioral complexity, polarity, flexible leadership, duality, dialectic, competing values, dichotomies, competing demands, ambidexterity, and so forth. It’s not hard to find a list of paradoxes for organizations or individuals. Merely ask any employee about the challenges they face in their job.

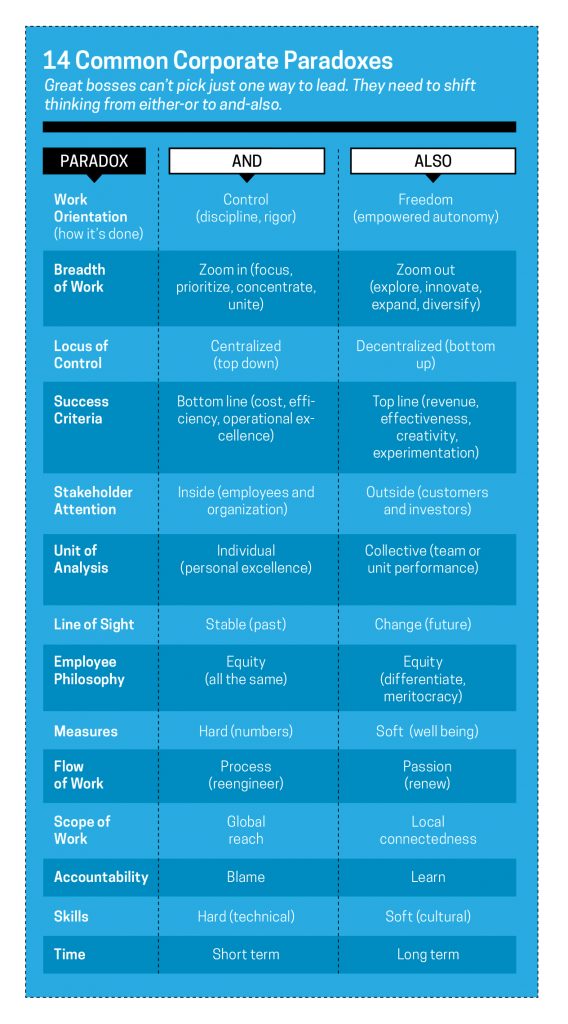

By listening, paradoxes or tensions often come out. But it’s helpful to be explicit about which paradoxes are most prevalent and require attention in an organization. We have prepared a list of common paradoxes below:

Leaders who recognize paradox become great bosses when they make these paradoxes explicit. We have done an exercise with executives where they select the top two or three most important paradoxes given business goals. Once a leadership team recognizes the paradoxes, the boss can help navigate the tension they cause.

Great bosses transcend paradoxes. They don’t ignore them or become stifled by them. They help employees recognize that there are inevitable tensions that exist in any successful organization—and that’s okay. Bosses then manage the dialogue to navigate these paradoxes.

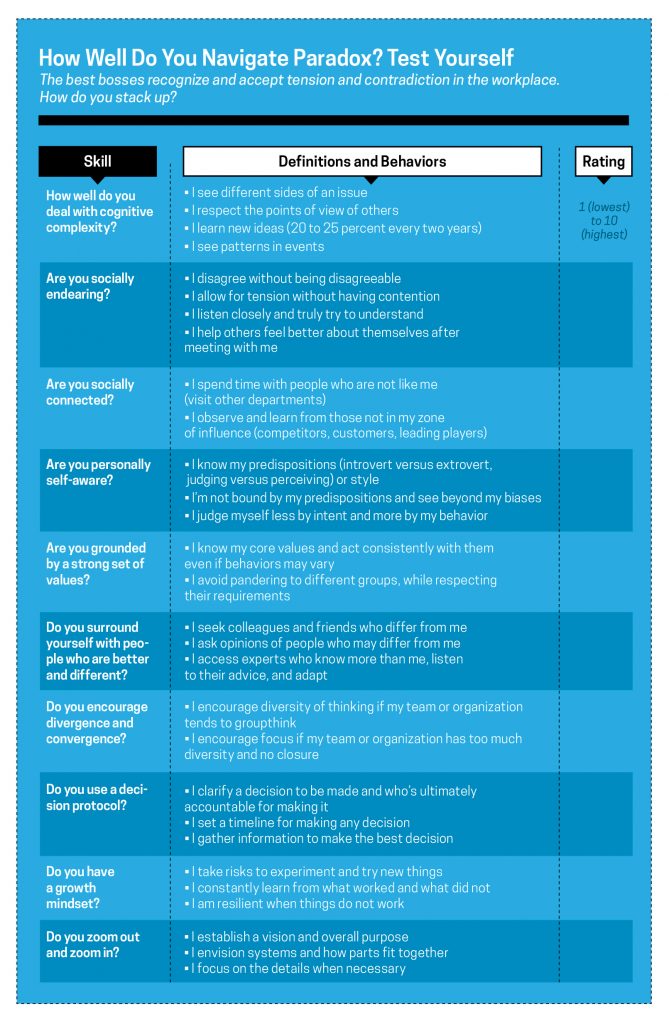

In our work, we have identified 10 personal skills of a paradox navigator that good bosses can master to help employees succeed. We have created this self-assessment navigator to demonstrate the specific leadership skills for navigating paradox:

When leaders accept, recognize, and navigate paradox, bosses emerge who can tolerate ambiguity and disagreement to make progress.

So, what do these three pivots mean for turning good leaders into great bosses? If you are a boss, see how well you understand and implement these three insights. If you are responsible for developing better bosses (trainer, coach, facilitator), make sure that you help leaders become bosses. If you are an employee, encourage your boss to master these pivots to more effectively mentor and lead you.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Dave Ulrich is the Rensis Likert professor at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan. He’s also a partner at The RBL Group, a consulting firm focused on helping organizations and leaders deliver value. In addition, he’s published more than 200 articles and authored more than 25 books.